European attitudes to immigration

by Dr Lindsay Richards

20 Sep 2016

Immigration continues to be one of the most topical and pressing political issues in Europe, with voters in many countries rating it high on the political agenda, and ‘radical right’ political parties making gains in many European countries. It is also likely that these attitudes shape the experiences of migrants themselves and influence the extent to which they are able to integrate into the ‘host’ society. It is evident, then, that attitudes to immigration have far-reaching consequences.

We are familiar with these consequences in the UK. The recent decision to ‘Brexit’ the European Union was thought to be largely driven by anti-immigration sentiment and in the wake of the referendum much has been written on the divided nature of British attitudes. It is all too easy to believe that people fall into two categories: those against immigration and those not. There is also the frequent suggestion that attitudes come in bundles and opposition to immigration is accompanied by nationalism, racism and hate crime. On the other hand, the remainers were portrayed as pro-immigration, liberal and open-minded.

But is such a simple picture of European attitudes to immigration realistic? We can investigate attitudes to immigration across Europe in greater detail than ever before with the latest round of the European Social Survey (ESS). What this data demonstrates is that judgements can be tentative and nuanced and public opinion cannot be reduced to those for and against immigration. When asked how many immigrants should be allowed to come and live in their country, for example, the most common answer is more often than not a middling “some” or “a few”.

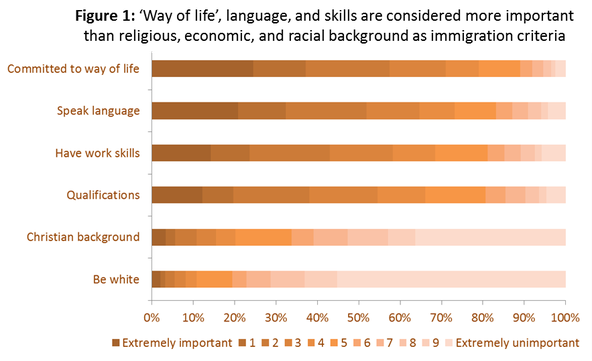

Further, it is not just a matter of thinking that borders should be open or closed: people hold opinions on the criteria they think should apply when deciding who to let in in. The following factors are rated as very important: immigrants should be committed to the receiving country’s way of life, should speak the language and have skills that enable them to find employment (perhaps people have taken on board the idea of the much-discussed Australian points-based system). On the other hand there are few people in Europe who say that skin colour or religion are important (see Figure 1).

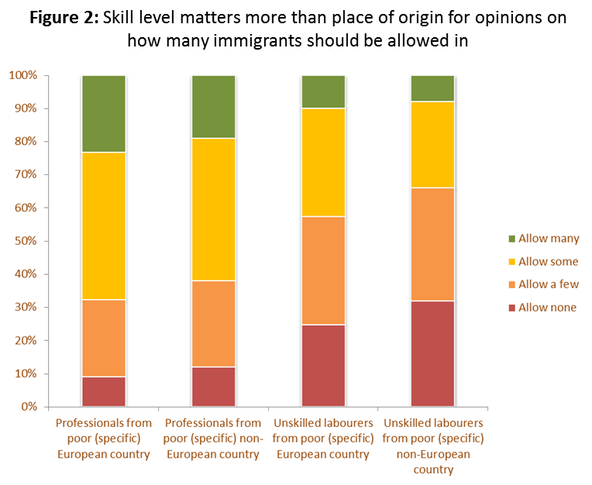

And confirming the importance of skills, the public also make clear distinctions about what type of migrants are preferred. When asked how many unskilled/ professional or European/ non-European people should be allowed to come in, people hold more favourable attitudes towards professionals and the place of origin seems to matter much less. Europeans are still preferred to non-Europeans but the difference is smaller than between the skilled and unskilled (see Fig 2).

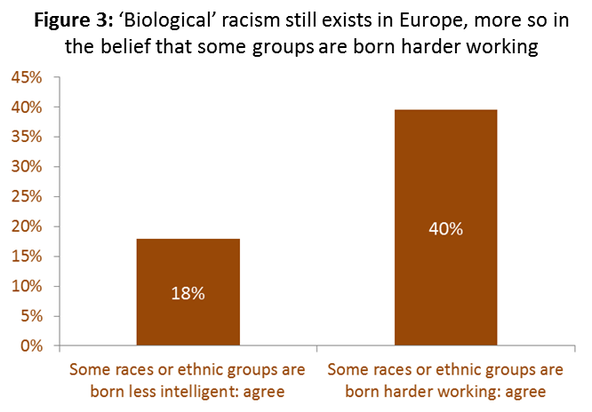

Does this emphasis on the skill level over ‘race’ of migrants give us reason to feel more positive about public opinion? Are we not quite as bad as we thought? It is true that prejudice based on skin colour or ethnicity is in decline, but might it be that racism has simply evolved? We may be living in an era where prejudice has taken on a more subtle and less blatant form with attitudes towards outsiders more comfortably expressed in terms of skills and lifestyles rather than skin colour or religion. Perhaps it is just a matter of asking the right questions to find out. The ESS also included some questions that allow us to get at the some ideas that might be associated with old-school, biological racism. For example, 18% of people in our European sample think that some races or ethnic groups are born more intelligent, and 40% think that some groups are born harder working (see Fig 3).

How can we explain why some individuals hold certain attitudes? One explanatory theory is that perceptions of threat shape our opinions, where the threat may be economic (they will take our jobs and houses) or cultural (they are just not like us). Indeed, evidence suggests that the economically vulnerable (for example with lower incomes and lower educational qualifications) hold less favourable attitudes, and that attitudes tend to be less favourable where the cultural distance is greater. The context is also likely to be important for shaping public opinion. How much, for example, do levels of democracy in a country matter? And what impact do events such as the migrant crisis or terrorist attacks have on public opinion?

These questions and more will be addressed in a two day conference on the 16 and 17 November 2016, to be held at the British Academy. The event, convened by @csinuffield and @robfordmancs, draws together experts on attitudes on immigration and addresses key issues including change over time, intergroup contact theory, realistic and symbolic threat, nationalism, Islamophobia, and support for the far-right. Register for the event here.

Lindsay Richards is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College, Oxford, and her primary research interests include social status and its influence on well-being and attitudes.