How looking at Bibles as objects transforms our view of the Reformation

by Dr Eyal Poleg

20 Jan 2021

Gutenberg and Luther, the printing press and the Reformation, are key turning points in world history. Their impact on non-European regions might be challenged, but their place in the history of the Bible seems unrivalled. Popular accounts, dating back to the 16th century, portray how early reformers sought to spread the Bible far and wide, placing it in the ploughboy's hand (to borrow a phrase from William Tyndale, who had done much to translate the Bible into English, and was subsequently burnt at the stake in 1536). Their religious zeal had led them to translate the Bible into common languages and disseminate it widely, despite the objection of Church authorities. And print, of course, was instrumental in that mass-dissemination of Bibles, with print shops producing Bibles in a multitude of sizes and prices to suit growing audiences.

Like all good stories, it mixes fact and fiction. Surveying hundreds of Bibles in manuscript and print form for my recent book A Material History of the Bible, England 1200-1553 made me grapple with, and often challenge, such turning points in the history of the Bible. Looking at Bibles from across the period proved instrumental. Bringing together both the Middle Ages and early modernity has put these turning points in their wider context, questioning their impact and unearthing gradual transformations, as well as fault lines, in the long history of the Bible in England. Common histories tend to look at the text of the Bible, exploring translation, language and choice of words. By looking at the Bible as a physical object and asking how these Bibles were made and used, one quickly moves away from these traditional narratives.

Beyond heresy

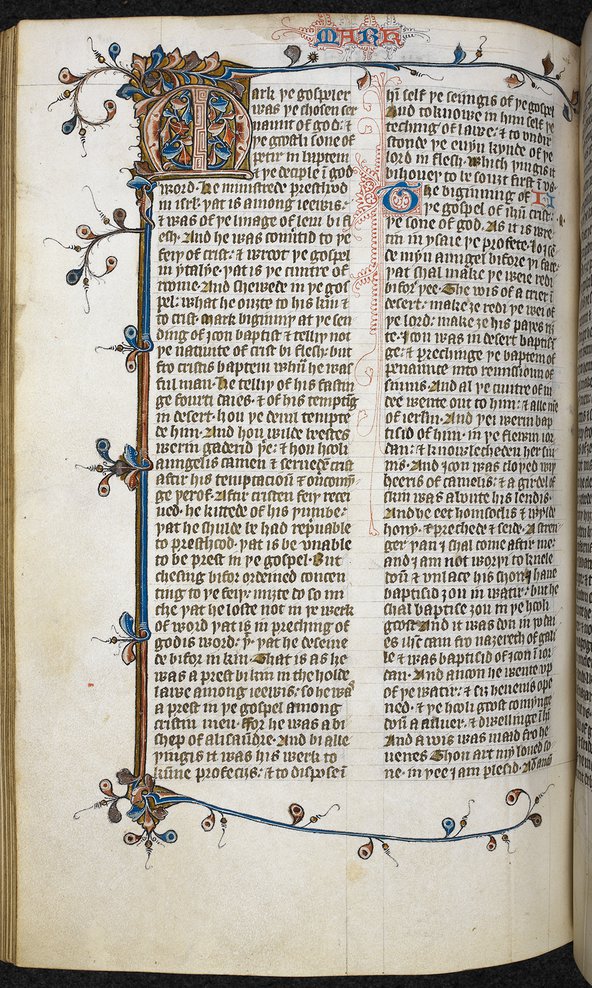

The Wycliffite Bible, the earliest translation of the entire Bible into English, exemplifies how looking at books as physical objects can rewrite traditional narratives. This Bible was compiled in the late 14th century by the followers of John Wyclif, an Oxford theologian whose opinions incurred the wrath of the English Church and whose followers were persecuted as heretics. By the 16th century this Bible was seen as an emblem of reform, evidence of English Reformation before Luther. Its surviving manuscripts, however, tell a different story. The Bible survives in over 250 manuscripts, making it the most prolific English book of the Middle Ages and questioning how widely or effectively it could have been censored. Wyclif is not mentioned once in the Bible that bears his name. The only explicitly anti-clerical element in the Bible, a lengthy introduction known as the General Prologue, exists only in a handful of manuscripts. Most Bibles are devoid of any heretical components and their known owners are nuns, monks, priests and devoted laypeople. Rather than evidence of heresy, they often serve as witnesses to a vibrant, and permitted, vernacular devotion which existed in nunneries and lay chapels prior to the Reformation.

Latin, English, or both?

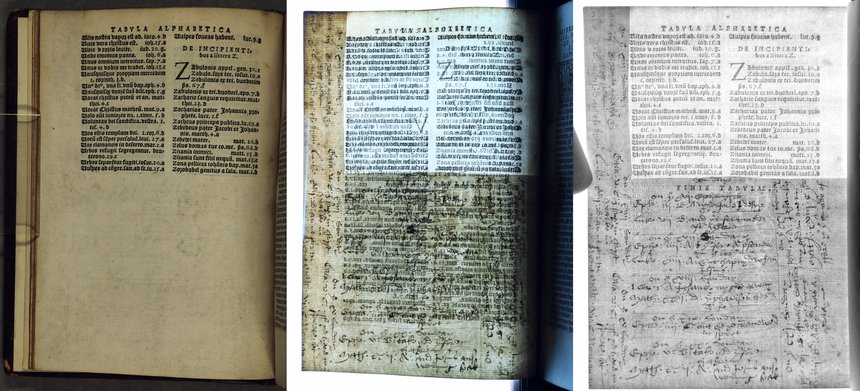

Through the prism of the production and use of Bibles, the course of religious reform in the reign of Henry VIII is anything but unidirectional; less a series of turning points and more a seesaw motion, as different factions in court sought to influence Henry into advancing, or retracting, religious reform. Unique evidence for this protracted process has survived in the pages of an early printed Latin Bible, the first Bible to be printed in England. Together with Graham Davis, Professor of 3D X-ray Imaging, we were able to virtually peel off pages pasted into the Bible more than 400 years ago. Underneath, liturgical notes were scribbled in a 16th-century hand, facilitating the use of this Latin Bible within licit English Bible reading, practiced between 1539 and 1549. These reveal how Latin and English merged in the liturgy of the last years of Henry VIII’s reign. Other annotation, hidden in the last page of the Bible, records a transaction with James Elys of London, who was hanged at Tyborne on 11 July 1552 as ‘the great pick purse that ever was, and cut-purse’, providing further evidence to the turbulent afterlife of the Bible.

The Great Bible as a useless book

The Great Bible is often seen as the monument of the English Reformation. Backed by Thomas Cromwell, it was to be purchased by every parish church across the realm. Its print quality and high-grade paper were beyond that of any English Bible hitherto, leading the production team to seek a Parisian printer, as no English printer was equipped for such a colossal task. Its materiality, however, had set in on a collision course with Church worship. While this immaculately printed (and expensive) book provided the Bible in English, most of the liturgy was still in Latin. While this book was to be kept at a place where parishioners would be able to consult it, the liturgy was still conducted primarily by the priest behind the rood screen. The result was confusion, misuse and uncertainties surrounding the use of the Bible, which incurred the wrath of priests and Church reformers alike. Most importantly, lay use of the Bible had aggravated Henry himself, who had retracted his hesitant support, decreeing against Bible reading by the lower classes. The luxurious hand-illuminated title page presented here is a unique, and extremely complex, image. Scientific analysis carried out with Paola Ricciardi, Senior Research Scientist at the Fitzwilliam Museum, has revealed its hidden transformations, including how, by pasting new portraits onto the page, Cromwell responded to the shifting politics of Henry’s court.

The examples of the Wycliffite Bibles and those printed in Henry VIII’s reign demonstrate the gradual and hesitant transition, much celebrated by Reformers, from Latin to English as the language of Bible and prayer. The same is true for print. In certain ways the layout of modern Bibles was consolidated by 1230. In a gradual move across centuries, reading aids that had been developed for trained professionals in medieval universities were deployed by lay men and women. This gradual transition, through technological innovations and religious reforms, was shaped by scholars and reformers, by craftsmen and readers, which together shaped the Bible as we know it today.

Dr Eyal Poleg is Senior Lecturer in Material History at Queen Mary University of London and was awarded a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship in 2008. Read more in his book ‘A Material History of the Bible, England 1200-1553’, published by Oxford University Press for the British Academy.