Why do some children experience psychotic symptoms?

by Dr Helen Fisher

17 Jun 2020

Have you ever had the feeling that someone was watching or following you and when you turned around, no-one was there? Have you ever thought you heard someone calling your name but then realised you were just imagining it? Have you ever thought other people knew what you were thinking? Have you ever thought your horoscope might come true? If your answer to any of those questions was ‘yes’, then you’ve had a psychotic experience!

Psychotic experiences are surprisingly common among the general public and are considered a much milder form of psychotic symptoms, which we usually associate with disorders such as schizophrenia. Psychotic symptoms include hearing voices that others cannot hear, having visions, intense feelings of paranoia and other unusual experiences. These can include believing that your thoughts are being read by someone, or that what you read in the newspaper or hear about on the TV has a special meaning for you. These symptoms are often referred to as hallucinations and delusions.

Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in children

Interviews conducted with children in large studies of the general population have found that around one in 20 children aged 12 reports psychotic symptoms despite having no diagnosable mental health disorder. That equates to at least one child in every Year 7 class! Although for some children these symptoms will be reasonably benign and disappear with time, for others they are extremely distressing and can lead to the development of a range of severe mental health problems, as well as self-harm and suicide attempts in adolescence and adulthood.

It is thus crucial to understand which children are most likely to develop psychotic symptoms and what might protect them from doing so. This will allow us to identify the most vulnerable children and provide them with the right help and support to prevent them from having such symptoms.

My team attempts to answer these questions by using data from large cohort studies of children born in the UK who have been repeatedly assessed as they grow up on a wide range of measures. This allows us to look back at what children who report psychotic symptoms had experienced earlier in their lives, as well as to look forward to what happens to them as they get older.

What makes children more susceptible?

Our research has shown that children who experience being abused or neglected by parents, are bullied by peers, or witness domestic violence are around two to three times more likely to develop psychotic symptoms than children without these early adverse experiences. This risk increases further if they experience multiple forms of victimisation. We have also found that children who grow up in cities tend to have psychotic symptoms more often than children living in smaller towns and villages. There is quite a lot of variability within cities, though; the children most at risk were those residing in areas where there was not much sense of community, a lack of trust between neighbours and much higher rates of crime. Some preliminary evidence also suggests that exposure to elevated levels of air pollution during childhood might partly explain why psychotic symptoms are more common among those living in cities. Additionally, we found that there are some differences in the way that genes are regulated between children who go on to have psychotic symptoms and those that do not.

Reducing the stigma

All of this research provides us with initial clues as to which children might be most susceptible to developing psychotic symptoms. Eventually, this will help us to effectively target interventions to reduce the likelihood of vulnerable children having these symptoms.

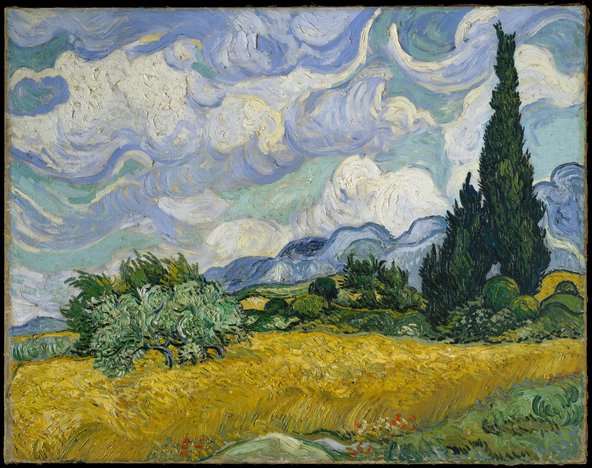

But what might such interventions involve? My team have found that having just one person to talk to about their feelings can protect children, even those who have experienced multiple forms of victimisation, from developing psychotic symptoms. Unfortunately, due to the persisting stigma surrounding psychosis and mental health more broadly, children often don’t feel comfortable talking to others about their feelings. This means they can suffer in silence for many years before they get help, which can allow psychotic symptoms to develop. Therefore, we believe it is absolutely crucial to reduce this stigma through increasing public understanding of psychotic symptoms. In collaboration with artists and young people, we have undertaken a series of immersive art and theatre projects such as an immersive voice-hearing art exhibition and a National Gallery Mental Health audio tour to give people a flavour of what it feels like to experience psychotic symptoms and encourage people of all ages to talk more about their feelings. As the well-known BT slogan says: “It’s good to talk!”

Dr Helen L. Fisher (@HelenLFisher) is a Reader in Developmental Psychopathology in the Centre for Society and Mental Health (@kcsamh) at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London (@KingsIoPPN). She received a British Academy Mid-Career Fellowship in 2018. Her research project ‘Uncovering the mystery of early psychotic symptoms: phenomenology, outcomes, and greater public awareness’ featured in our British Academy Virtual Summer Showcase.

More information about hearing voices and other psychotic symptoms and ways to access support for these experiences: