What can we learn from the history of charity and charity shops?

by Dr George Gosling and Dr Georgina Brewis

16 Nov 2020

Why is the history of charity important?

Most people encounter charities and voluntary organisations on a day-to-day basis – though they may not always realise that they do. Over half of UK adults have given money to charity in the past year and a similar number have donated goods, perhaps for sale through a charity shop or to a foodbank. Others might engage as volunteers, by signing petitions and supporting campaigns, by playing for a local sports club, or through visits to museums and other heritage sites. We benefit from medical breakthroughs funded by charity, attend universities, schools or hospitals underpinned by philanthropy, and seek advice on topics ranging from mental health, employment rights or the best consumer products from voluntary organisations. Voluntary organisations work with vulnerable and disadvantaged social groups in ways too numerous to mention. In addition, the UK voluntary sector employs nearly a million people – most of us will know someone who works for a charity.

Charities matter, and their history matters too. We can’t understand the history of the UK without examining the central role played by voluntary action. It has helped to forge our national systems of education, health and social care, form our cultural, leisure and sporting lives and shaped our relations with the wider world. Yet, the archives of voluntary organisations are uniquely vulnerable – they lack both the legal protection afforded to records produced by government and the financial resources and support networks available to other private archives.

Only a very tiny number of British charities have professional archivists. Some have deposited or donated records to a university or the local authority’s records office, but many more retain archives in-house. The conditions of how these records and objects are stored and preserved, the extent of cataloguing and the nature of access varies hugely across the sector.

The long history of fundraising shops

Let us take one of the most familiar sights on UK high streets – the charity shop – as an example. Research using archives and material objects has uncovered a longer and more varied history of charity shops than we often imagine.

As far back as the 1960s, there have been news stories asking if there were now ‘too many’ charity shops on UK high streets. In the late sixties, local branches of charities turned to second-hand shops as a means of fundraising. The success of Oxfam’s flagship store on Broad Street in Oxford, opened in the run-up to Christmas 1947, demonstrated that organisations could now be more ambitious than the older traditions of jumble sales and church fetes. However, the charity shop was not invented in 1947. During the Second World War, charities including the British Red Cross had opened temporary stores. These efforts brought together aspects we are familiar with from today’s charity shops: second-hand goods sold to raise money for a specific charity within a fixed space that also served a promotional purpose. There is, however, a longer history, which reveals that charity-run shops did not always operate on this model. Indeed, the earliest known fundraising shop sold flowers in Mayfair from 1870 to support a mission in East London.

Beyond fundraising?

The late-19th century saw the Salvation Army operate two very different models of charity retail. Its ‘salvage stores’ were part of its work to help the poor emerge from Darkest England by enabling them to furnish their homes at a low cost, with little if any attention to what was raised, echoing schemes sometimes referred to as ‘charity shops’ that had sold subsidised foods since the late 18th century. Meanwhile, the Salvation Army’s Trade Department ran a lucrative line of high-quality branded, purpose-made goods – everything from musical instruments to razor blades – that gave work to Salvationists as producers and retailers. The department kitted customers out with everything they needed to live a good Salvationist life.

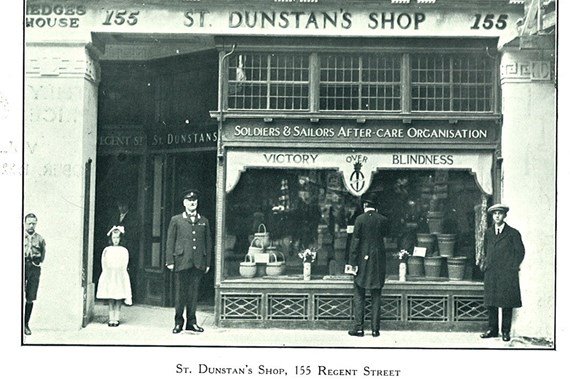

A century ago, the most common charity-run shops were those selling craft goods made by people with disabilities. These facilitated the employment of disabled craftspeople and offered customers a way of showing their support, but they rarely turned a profit. That profit-making was not a factor in whether such shops were considered successful, is a reminder to us that charity shops have a variety of social and community functions, of which fundraising is just one. Today, this might be easily forgotten if it were not for the evidence preserved in charity archives. Next time you are browsing the shelves of your local charity shop, you might reflect about this longer lineage.

Dr George Gosling (@gcgosling) is Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Wolverhampton. Dr Georgina Brewis (@DrGinaB) is Associate Professor in the History of Education at University College London. She received research funding for an Academy Research Project in 2014. Her research on charity archives was featured in the British Academy Virtual Summer Showcase and they both hosted a virtual tour on the histories of charity shops as part of the 2020 Being Human Festival, Shopping for a cause?

You can read more about the project at Charity and Voluntary Sector Archives.

Lead image: Reproduced courtesy of Oxfam. Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, MS. Oxfam DON/1/3.