Religion and Community in the Roman Near East: Constantine to Mahomet

Wed 27 Jan - Wed 10 Feb 2010, 17:30

Speaker:

Professor Fergus Millar FBA

I. The Legacy of Alexander and the Bible. A Greek Christian World?

When the Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity, acquired control of the Eastern provinces of the Empire and called the Council of Nicaea in 325, it was over six and a half centuries since Alexander had conquered the Near East. When the forces of Islam invaded in the 630s, Greek had been the primary public language there, from the Mediterranean to the Tigris and from the Taurus Mountains to the Red Sea, for almost a millennium.

But how deeply had Greek culture penetrated, and was the Christian Church in the Near East wholly Greekspeaking? What 'resistance' was offered by either an Aramaic or Syriac speaking population, or by paganism? Where do the Jewish and Samaritan inhabitants of Palestine fit in? This long apparently 'Greek' phase in the Near East demands attention.

II. Jews and Samaritans in a Greek Christian World

In the first few centuries CE, a network of Greek cities came to cover almost all of Palestine, and by the sixth century more than fifty of these places had bishops, who preached and wrote in Greek. In this context, what forms of religious, social or cultural self expression were open to Jews or Samaritans?

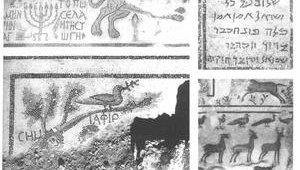

In the fourth–sixth centuries churches were built almost everywhere – but so also were Jewish and Samaritan synagogues – and it was these, not the churches, which produced elaborate representational art on their mosaic floors. Jews also produced the vast corpus of rabbinic literature in Hebrew or Aramaic. But how separate was Jewish life in reality from its gentile environment? Should we think of separation into distinct geographical zones, of peaceful coexistence, or of communal conflict?

III. Syrians and Saracens: Alternative Christianities?

Aramaic, in various dialects, persisted as a spoken language all through the centuries of GraecoRoman rule. But, while Hebrew and Jewish Aramaic were longestablished languages of culture in which religious texts were composed, at the moment of Constantine's conversion there was not a single community anywhere in the Roman Near East where Greek was not the dominant public language.

Christian literary composition in Syriac, which in origin was the Aramaic dialect and script used at Edessa, had however already begun before Constantine. The subsequent emergence of Syriac as a major language of Christian literary culture, and as expressed in the many beautiful contemporary manuscripts which survive, is of huge significance. But what was the role of Syriacspeaking Christianity in relation to Greek, and to the profound theological divisions of the time? Was it in Greek or in Syriac that the Bible and monotheism were transmitted to the Arabs of the desert?

About the Speaker

Fergus Millar was Camden Professor of Ancient History at the University of Oxford from 1984 to 2002. He is the author of The Roman Near East, 37 BC–AD 337 (1993) and A Greek Roman Empire: Power and Belief under Theodosius II, 408–450 (2006). He was awarded the Kenyon Medal for Classical Studies in 2005. Currently Senior Associate of the Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, Oxford, he is writing on the linguistic, cultural and religious history of the Roman Near East in the fourth to sixth centuries.