Published in British Academy Review, Issue 12 (January 2009).

The print version of this article can be downloaded as a PDF file.

Hitherto little has been known about the source of the benefaction which established the Schweich Lectures of the British Academy. The lectures were named in memory of Leopold Schweich and were to be ‘for the furtherance of research in the archaeology, art, history, languages and literature of Ancient Civilisation, with special reference to Biblical Study’. The Academy’s records from the time indicate that Leopold Schweich ‘of Paris’ had recently died in 1906, and Israel Gollancz, the first Secretary of the Academy, described the donor, his daughter Miss Constance Schweich, as ‘my friend’. One could also infer from the size of the gift – £10,000, which in today’s money would be equivalent to fifty or more times that amount – that she was a woman of considerable means, probably as a result of her father’s bequest to her.

Searches of the Internet (by Google™) have, however, produced leads to a variety of source material, which makes it possible to place the Schweich family in their social and historical context, or rather contexts. There remain many gaps, but the basic outline is now clear.

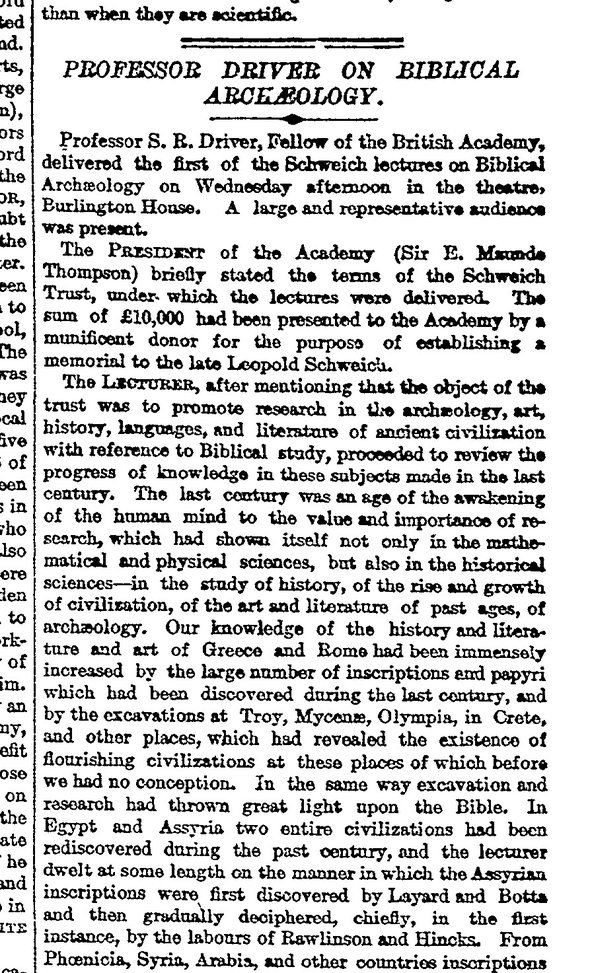

Leopold Schweich must have been born about 1840 and probably came from a Jewish family in Kassel, Germany, like the better known Mond family, with whom he and his children had a variety of connections. He is described as a ‘Kaufmann’ (merchant) and in February 1862 he married Philippina Mond (1840–73), the sister of Ludwig Mond, who was to become a great chemist and industrialist in England, being the founder or joint founder of the companies which eventually became ICI. J.M. Cohen, the biographer of Ludwig Mond, had access to a vast archive of the latter’s correspondence, which included, it seems, a good deal of information about the Schweichs [note 1]. From his incidental references to Leopold it is possible to fill out what is known of him from other sources, though detailed information about his parents, birth and home is still lacking. There may be more in the archive that Mond’s biographer saw no reason to include. A photograph from 1861 shows Leopold with Ludwig Mond, Ludwig’s future wife and her parents.

Figure 1. At the Löwenthals’ in 1861. Back row, left to right: Leopold Schweich, Frida Löwenthal, Ludwig Mond. Front row: Frida’s mother and father. Photo from Cohen, ‘The Life of Ludwig Mond’ (opposite p. 41).

Leopold was in Cologne before his marriage and planned to make it the family home. The wedding took place in the Mond home at Kassel with a rabbi present and the honeymoon was in Paris. He was a successful businessman in the international jewellery trade, and achieved some wealth, but he was regarded by the Monds as unreliable. He had a reputation as a bon viveur and seems to have needed good entertainment from the more withdrawn Ludwig on a visit to Utrecht in 1863. The family were still in Cologne in 1865 and Leopold attended Ludwig Mond’s wedding in October 1866.

Leopold and Philippina had two children before her early death in 1873, Emile (b. 1865) and Constance (b. 1869). Possibly by the time of Constance’s birth the Schweichs were already in Paris. In the 1870s Ludwig, who had by this time settled in the north of England, lost faith in Leopold and increasingly took his children under his wing: Leopold’s absences on business trips abroad (even to Russia), as well as the death of Philippina, seem to have played a part in this. They remained in contact and two letters from Leopold to Ludwig (and in the first case also his wife Frida) Mond, dated April and September 1884, survive in the ICI (Brunner, Mond) archives in Chester [note 2]. These provide us with his address in Paris at the time, 8 Rue Martel, near the Gare du Nord and Gare de l’Est, and from the printed letterhead of one we also learn that this was the base for ‘Schweich Frères’, presumably his family business.

Figure 2. Leopold Schweich’s house in Paris, 8 Rue Martel. Photo: Graham Davies.

The same archive contains two letters (dated August and September 1884) from a Louis Schweich to Ludwig Mond, one of which carries the address ‘119 (altered from ‘107’) Boulevard de Magenta’, which was nearby: he is presumably Leopold’s brother, or one of them. There is also a letter, dated June 1884, from Emile Schweich to Ludwig Mond, written from Zurich, where he was a student. The letters are handwritten and when/if they are fully deciphered they will provide interesting further insights on the Schweichs’ family life and their relations with the Monds. Already it is possible to pick out a reference to ‘meine geliebte Constance’ in one of Leopold’s letters. The last we know of Leopold before his death is that he invested in the company which his son Emile set up in Jamaica, probably in the 1890s.

Emile was educated at the Collège de Sainte Barbe and the Lycée Condorcet in Paris and then at the University of Zürich. He became a successful chemist like the Monds and was given a job in the family firm. At some point he took the name Mond, being known as Emile Schweich Mond. He was Vice-President of the Chemical Society (1929– 1931) and its Treasurer from 1931 until his death in 1938. His obituary contains a story from his student days which reflects his father’s strictness with him (but also perhaps a sense of humour).

Constance had also joined the Monds in England by 1894, where it is said that she lived with them as ‘almost a daughter’. In 1892 she accompanied the renowned Jewish patron of culture Henriette Hertz on visits to Bayreuth and Frankfurt. Hertz, who was now 46, apparently acted as a chaperone to the younger Constance. Their association no doubt came about through the Monds, as Hertz and Frida Mond had been at school together in Cologne. Hertz and the Monds were in regular close contact from 1868 onwards. In her later years this continued and she was often with them in London and in Rome until her death in 1913.

Both Emile and Constance were present at the twenty-fifth anniversary of the foundation of Brunner, Mond in 1898 (Figure 3). Both of them were to marry children of James Henry Goetze, a London coffee merchant. This was also the family of the Violet who became the wife of Alfred Mond, Ludwig’s younger son. Emile’s wife Angela (with whom he had five children) is likely to be the Angela Mond who founded the British Academy’s Italian lectures in 1916. Frida Mond (née Löwenthal), Ludwig’s wife, was another benefactor of the Academy, endowing the Warton and Shakespeare lectures in 1910 (in memory of Ludwig, who died in the previous year?) and the Gollancz Lecture, which was first given in 1924, the sixtieth year of Israel (now Sir Israel) Gollancz, whom she greatly admired. Frida Mond died in 1923, and the endowment was a bequest in her will. Her friend Henriette Hertz had made a benefaction to the Academy in her will: the Henriette Hertz Fund supports the ‘Master Mind’, Philosophical and Aspect of Art lectures.

Figure 3. Celebration in 1898 to mark the 25th anniversary of the foundation of Brunner, Mond: outside the Orangery at Winnington Hall. Back row, left to right: Alfred Mond; Emile Schweich Mond; Constance Schweich; Edith, future wife of Robert Mond; Robert Mond; Sigismund Goetze. Front row, left to right: Violet Mond; Henriette Hertz; Ludwig Mond; Frida Mond. Photo (cropped) from Cohen, ‘The Life of Ludwig Mond’ (opposite p. 192).

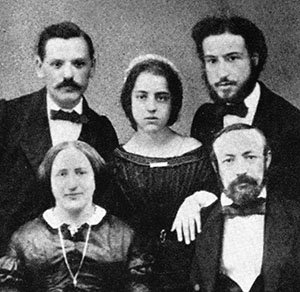

The Schweichs, the Monds and their British Academy endowments.

Constance Schweich

Constance did not marry until 1907, when she was 38. It is possible that she had taken over Henriette Hertz’s lifelong abhorrence of marriage, but if so her father’s death seems to have changed matters. She married Sigismund Goetze, a well known painter who had long (since 1891) been known to the Monds (he is also in the 1898 photo, not far from Constance). He was later commissioned to paint murals at the Foreign Office during the First World War.

At the time of their marriage Goetze bought the lease of Grove House, a mansion at the north-west corner of Regent’s Park, opposite St John’s (Wood) Church and a short distance from the Mond residence in Avenue Road. Papers about the house are preserved in the City of Westminster archives, and include a photograph of a painting of Constance in Florentine dress by her husband (1911; Figure 4), a wartime photograph of her, and photographs of a garden party at the house in July 1939 at which the Queen (i.e. the Queen Mother of more recent times) was present. The house, to judge from later sales and bequests (see below), was evidently full of valuable antiques and paintings [note 3]. Constance had a reputation as a gifted pianist: she gave concerts at Grove House and accompanied Segovia on several occasions. But their company was not universally appreciated, it seems: the writer Arthur Symons (1865–1945) wrote to his wife in 1912 that it had been good to get away from ‘the Gu-ts’, which seems to have been a nickname for them.

Figure 4. Photograph of a painting of Constance in Florentine dress by her husband, Sigismund Goetze (1911). Courtesy of City of Westminster Archives Centre.

In the 1940s, after her husband’s death in 1939, Constance disposed of a number of items: a 15th-century manuscript of Pseudo-Augustine, now in the Henry Davis Collection at the British Library (the catalogue also mentions her as the former owner of manuscripts now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge); a wooden statue of St Christopher c. 1500, another of a female saint, four female saints c. 1480–1500, a 17th-century St John, a 19th-century St Helen, a 15th-century angel, a 19th-century Assumption of the Virgin and a 16th-century Christus lapsus, all now in the Fitzwilliam Museum. In 1944, perhaps from the proceeds of the sale of (some of) these items, Constance set up a fund, named after her, to improve public parks by the erection of works of ornamental sculpture. It is referred to in Hansard for 23 July 1957, in connection with a decision to install an ornamental fountain in Hyde Park (‘Joy of Life’ by T. B. Huxley-Jones), which was to be paid for by the Constance Fund. Much more information about the Fund and the family is given in a booklet by M. Holman about the sculpture of Richard Rome that was inspired by his ‘Millennium Fountain’ in Cannizaro Park, Wimbledon, which was also paid for by the Fund [note 4]. The original idea for the Fund had come from Sigismund Goetze, and Constance later recalled the circumstances where it was first conceived:

‘We were touring in Italy and stopped at Bologna to see [Giambologna’s] famous Neptune Fountain which is erected in the midst of the picturesque flower market. The day was a perfect one, and the bronze seemed alive under the sprinkling water, bathed in sunshine, against a dazzling background of exquisite flowers. We were spellbound by the loveliness of the scene, to which a busy crowd added a peculiar charm. And it set my husband wondering why our sculptors in England are so rarely given the opportunity of displaying their works in open spaces, in parks and recreation grounds, where the man in the street can enjoy them and, may be, gain love and understanding for works of lasting value and real artistic merit.’

In addition to those already mentioned, the Fund paid for fountains in Regent’s Park (‘Triton’; Figure 5), Victoria Park in Bethnal Green (‘Little Tom’) and Green Park (‘Diana of the Treetops’), as well as elsewhere in the UK.

Constance had moved out of Grove House following bomb damage in 1941, and at the end of the war the lease was reassigned and she lived at 40 Avenue Road. In her will (proved 4 April 1951) Constance left money to the Royal Academy of Music to assist promising performers on the piano or a stringed instrument to acquire an instrument for use in their first recital in a London concert hall. She also bequeathed a number of further items to the Fitzwilliam Museum: a bronze cast of Perseus by Alfred Gilbert, an 18th-century Pieta and a Book of Hours (Ms. 9.1951). These were delivered to the museum by a Mrs May Cippico, who is described (in relation to the Pieta) as Constance Goetze’s niece, most likely a (married) daughter of her brother Emile. It seems that the Goetzes had no children of their own.

The Schweich Lectures

With her close connections to the Monds it is not at all surprising that Constance Schweich made a benefaction to the Academy, only perhaps that she was the first. It remains unclear why exactly she wanted to support research into antiquity for the sake of Biblical study. Her Jewish origins may have played a part, but her relatives generally gave their support to the study of modern European culture. An interesting and perhaps significant exception is her cousin Robert (later Sir Robert) Mond, Ludwig’s elder son. Although primarily an industrial chemist like his father, he had a profound interest in Near Eastern archaeology, especially after being forced for health reasons to spend several winters in Egypt from 1902. He both participated in excavations and supported them financially and he was the major financial supporter of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem in the 1920s, including Dorothy Garrod’s work at the Mount Carmel Caves. The offer of Constance’s benefaction came with detailed provisions for its use, including the support of excavations and the distribution of any objects found, and this would be a lot more intelligible if she were being guided by someone with the interests of Robert Mond. Although the key letter offering the gift is missing from the Council of the Academy’s minute-book, some private correspondence between her and Gollancz from early in 1907 is preserved in the Gollancz archive at Princeton University and it shows that both of them were close to him. In a letter dated 10 January 1907 Constance wrote:

‘I was so glad that you went to Paris with my darling auntie [Mrs Frida Mond] and poor Robert. My thoughts were permanently with them during the sad days, which ought to be days of joy for all! I am sure your sympathy and friendship was a great help and that the little ones were more than happy with you. Irene is a great favourite of mine…’ [note 5]

Robert Mond’s wife had died tragically late in 1905, leaving him with two young daughters. The likelihood of his interest in the Schweich project is increased by his involvement in the publication in 1906 of the first substantial volume of Aramaic Papyri Discovered at Assuan (the texts better known as the Elephantine papyri). According to his own introductory Note, Robert Mond was telephoned about a discovery of papyri during his own excavations at Thebes in the spring of 1904 and he immediately travelled to Aswan and ‘acquired them with the intention of presenting them to the British Museum’. When the Egyptian authorities virtually insisted that he present them to the Cairo Museum, he made it a condition that he should have the right of publication. The Oxford scholar A.H. Sayce had seen them at Thebes and agreed to edit them, subsequently with the help of A.E. Cowley. Mond actually financed the elaborate publication of the texts and seems to have been behind the inclusion of two scholarly appendices. Although the documents included were only contracts, and not the even more interesting letters and offering-lists discovered later, Sayce found plenty of biblical interest to write about in his introduction and, rather prematurely, concluded that this new evidence supported the existence of monotheistic belief at Elephantine. In other words, at the very time when the Schweich bequest was being made, Mond was in direct contact with Sayce about a discovery which was already perceived to be of considerable biblical interest (and which was to be the subject of the Schweich Lectures in 1914). Mond presented a copy of the volume to the Society of Biblical Archaeology, of which Sayce had been the President since 1898, and became a member in November 1907. One might indeed wonder whether the requirement in the Schweich Trust Deed, which followed closely the terms proposed by the donor, that ‘all scholars of whatsoever School of thought’ should be eligible for appointment, was originally intended to ensure that, in this highly controversial field, conservatives like Sayce should be chosen to lecture as well as mainstream Old Testament scholars like S. R. Driver. If so, it was only successful in a small way: Sayce never gave the Schweich Lectures and the only real conservative to do so in the early years was E. Naville in 1915.

Notes

- The Life of Ludwig Mond (London: Methuen, 1956).

- Brunner, Mond and Co. Ltd Archives, in the Cheshire and Chester Archives, DIC/BM/7/5, cited with permission.

- See also P. Hunting, A Short History of Nuffield Lodge, Regent’s Park (King’s Lynn, 1974), pp. 25– 31.

- Embodying the Abstract: The Sculpture of Richard Rome (London, 2007).

- The original letter is in the Sir Israel Gollancz Correspondence, Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library, and is cited with permission.

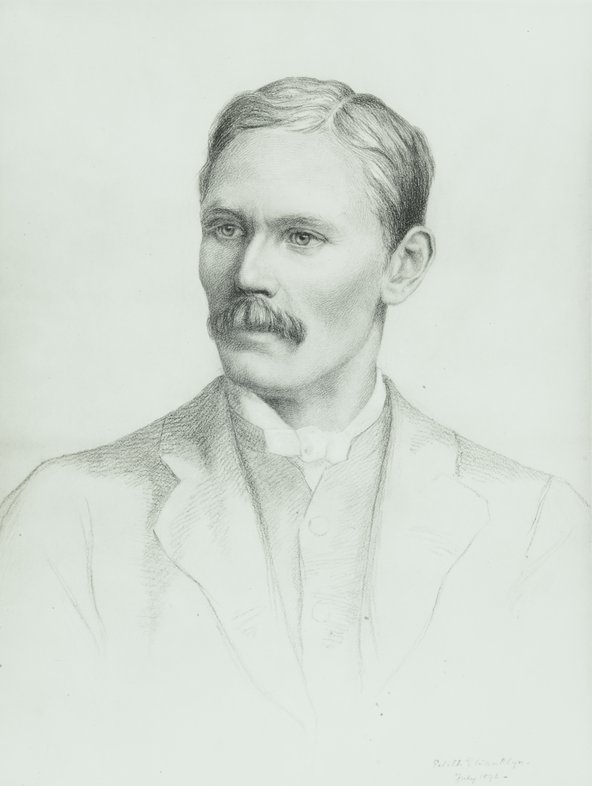

The inaugural Schweich Lectures were given in 1908 by Canon S. R. Driver on ‘Modern Research as illustrating the Bible’. The Schweich Lectures remain a highly regarded forum on the Bible and ancient civilisation. Each lecturer delivers three lectures, which are then published together in book form.

Professor Davies is Professor of Old Testament Studies at the University of Cambridge, and a Fellow of Fitzwilliam College. On 4 November 2008, he lectured on ‘Archaeology and the Bible – A Broken Link?’.

Published in 2011 in The Schweich Lectures and Biblical Archaeology, by Graham Davies

Supplement (January 2022)

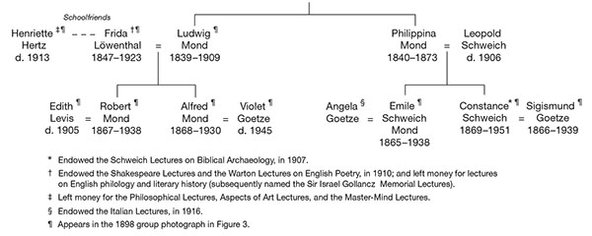

The first course of three lectures in the Schweich Lectures series was delivered in 1908 by the Revd Canon Samuel Rolles Driver, Regius Professor of Hebrew at the University of Oxford, and a founding Fellow of the British Academy.

The three lectures on ‘Modern Research as illustrating the Bible’, held on 18 and 30 March and 2 April, were all generously written up in The Times. The beginning of the newspaper report on the first lecture is illustrated.