A better politics could lead to more interest from citizens

by Professor Gerry Stoker

20 Jun 2012

In January 2012 Gerry Stoker published his British Academy Policy Centre report for the New paradigms in public policy project, called ‘Building a new politics?’ Here he discusses his most recent findings which suggest that in the right circumstances voters could become more engaged in politics.

Of late, politics and politicians have not been presented in a good light. The Leveson Inquiry has exposed politicians – even the Prime Minister – as having courted representatives from the Murdoch press; Jeremy Hunt, Secretary of State for Culture, Olympics, Media and Sport, is mired in controversy over whether or not he really knew his special adviser was communicating too closely with Sky employees on the BSkyB bid; Baroness Warsi, Minister without Portfolio, is the subject of a ‘sleaze’ investigation over an accommodation expenses claim. The negative news stories roll on, and feature politicians of all hues.

The 2012 Audit of Political Engagement in Britain characterises citizens as disgruntled, disillusioned and disengaged. It found that interest in politics had fallen to an all time low of 42% despite all the events and challenges experienced by the UK. It goes on to comment: ‘when only a quarter of the population are satisfied with our system of governing, questions arise about the long-term capacity of that system to command public support and sustain confidence in the future’.

These findings could simply be seen as depressing but there are grounds for hope. In Building A New Politics published by the British Academy earlier this year I examined how we might set about encouraging a much-needed positive response to politics, and how citizens might be encouraged to get engaged. Some new research funded by the ESRC and conducted by myself and Colin Hay (Sheffield) with colleagues at the Hansard Society suggests some real reasons to be positive on this front: given the right trigger it appears that citizens – particularly younger voters – may be willing to step up their level of interest in politics.

In certain circumstances, citizens’ interest in politics can change. Firstly, although many people do not really want to engage, there’s an argument that if politics becomes really bad, in terms of the levels of corruption by special interests or self-serving behaviour from politicians, more citizens might get involved. On this line of reasoning, if the negative triggers are strong enough the silent majority will rise up to kick out the rogues. Another line of argument claims the opposite, that what is needed to get citizens involved is a positive trigger, a sense that politics could be better, less rigged and where the views of citizens might come to matter in a way that they do not now. In those circumstances people would be more willing to lend their interest and voice to political proceedings.

To test for conditional attitudes toward involvement in politics in Britain we put together a representative sample survey and included two questions reproduced here.

“If politics were MORE influenced by self-serving politicians and powerful special interests do you think that you would be more or less interested in getting involved in politics?

At another point in the survey we asked:

“If politics were LESS influenced by self-serving politicians and powerful special interests do you think that you would be more or less interested in getting involved in politics?”

We could then sort the answers. First, we identified those whose response was the same to both questions: those who stayed interested or uninterested regardless of the preamble about whether politics was more or less influenced by self-serving interests. We say they have fixed preferences in that neither positive nor negative triggers would solicit from them a higher or lower propensity to be active politically.

We then distinguished between those who changed their response as a result of the negative trigger of (if politics were more influenced by vested interests) and those who were influenced by apositive trigger (if politics were less rigged and more open).

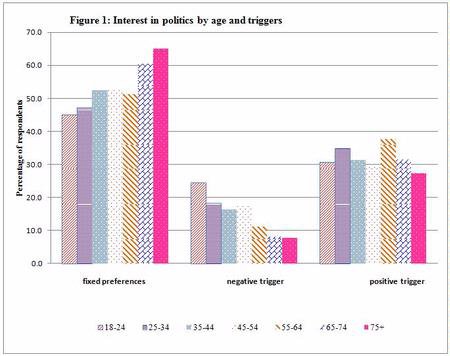

For the population as a whole we found that just over half were fixed in their preferences. But that of course means the other half of citizens could be persuaded to shift to greater interest in politics. For those who changed their response, the positive trigger proved twice as powerful as the negative trigger in stimulating a change of interest (Table 1).

Table 1: Interest in politics by age and triggers

Age Range

Fixed Interest %

Negative Trigger %

Positive Trigger %

Numbers in sample

18-24

44.8

24.5

30.6

245

25-34

47.1

18.2

34.7

340

35-44

52.3

16.3

31.3

294

45-54

52.6

17.7

29.7

293

55-64

51.3

11.1

37.6

271

65-74

60.3

8.2

31.5

232

75+

65.0

7.7

27.2

169

All ages

52.4

15.4

32.2

1844

Source: Audit of Political Engagement Survey, December 2011 and January 2012 (NB: percentage figures are rounded)

Going back to the two opposing explanations of interest in politics, it looks as if there are more citizens whose views fit with the idea that if only we could give the impression that politics was more open and less rigged, then the increase in interest would follow.

We also discovered a noteworthy age pattern to the responses. Some 6 in 10 of the age bracket 65-74 year olds had a fixed interest in politics compared to only just over 4 in 10 of 18-24 years old. The pattern holds as you go up through the age range. Younger citizens are less fixed in their pattern of interest and as a result more likely than older age groups to be provoked into greater political action.

However there is a potential sting in the tail. The impact of the triggers for greater engagement are more evenly matched for younger citizens, with both positive and negative stimuli making a difference, whereas higher up the age range it’s clearly the positive trigger that is making much more of an impact. Many younger citizens will get involved if things get even worse, although a few more would engage if politics could be made more attractive. For older generations the trigger for greater involvement would have to be a more positive politics.

The survey findings are encouraging to those who fear for our democracy if too many citizens have no interest in politics. The good news is that around half of citizens could get more interested in politics in the right circumstances and younger groups of citizens are more open than others to shifting their stance and getting involved. Generally a positive trigger in terms of offering a better politics looks more likely to make a difference.

The dark cloud is that this factor holds less strongly for the younger generations. But even that cloud might have a silver lining: if we could get citizens to believe that politics could be better, then many more from all age groups would be prepare to step forward. If on the other hand its image goes further downhill the younger generation might step in from sheer frustration and sort it out.

Gerry Stoker is Professor of Politics and Governance at the University of Southampton and author ofBuilding a new politics?

Relevant information:

Download the report Building a new politics?

Find out more about the New paradigms in public policy project

Find out more about the project Anti–Politics: Characterising and Accounting for Political Disaffection>