Devolution to the North East: will it finally happen?

by Akash Paun

5 Dec 2016

Local government representatives, academics and others from the north east of England gathered in Newcastle earlier this month to discuss the history and future of devolution initiatives in the region. This was the first in a series of events organised by the British Academy across the country as part of the Academy’s Governing England programme. Akash Paun reports on the proceedings.

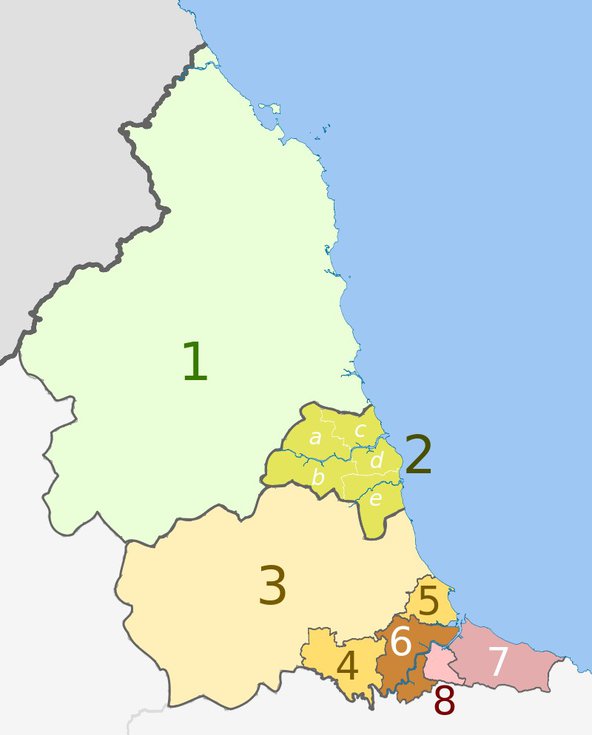

The discussion at Newcastle’s Discovery Museum took place in the context of the recent rejection of the North East Devolution Agreement, negotiated in 2015, between the UK government and the seven local authorities (areas 1-3 in the map below) that comprise the North East Combined Authority (NECA). While Newcastle, Northumberland and North Tyneside (areas 1, 2a and 2c) backed the proposals, the plan was rejected by County Durham, Sunderland, Gateshead and South Tyneside. This latest setback for devolution in the north east follows the rejection in 2004 (by 80% of voters) of a proposed regional assembly for the wider North East administrative region.

The 2015 plan was for NECA to take on greater responsibility for various strategic economic functions such as transport, housing and skills. The UK government had pledged an additional £30m per year to support this. The devolution deal also established a commission on health and social care integration, and raised the possibility of future devolution in areas such as climate change. As part of the deal, an elected mayor was to take office in May 2017 to lead the combined authority. Discussions are now ongoing about a new ‘Greater Newcastle’ deal between the three councils who backed the package and the Department for Communities and Local Government.

Meanwhile, in Tees Valley, south of the NECA area, five authorities (areas 4-8) are pressing ahead with their own devolution agreement, with the first election of a mayor for the region due to take place in May 2017. Here the deal was described by one participant as focussed more narrowly on economic development, with powers being devolved from Whitehall over employment and skills, transport, planning and investment.

Geography lessons

One reason why devolution to the north east has run into repeated difficulties is the lack of consensus over the appropriate geographical area to cover. This was a major problem in 2004, when the proposed regional assembly would have covered a wide territory (areas 1-8) that lacked either a shared identity or an integrated regional economy. Since 2004, the Regional Development Agencies and Government Offices across England have been abolished. Consequently, the wider North East administrative region was generally regarded at our event as defunct as a tier of governance, used only for statistical purposes to calculate trends such as regional economic growth and employment.

The more recent NECA and Tees Valley deals were designed to cover what the government calls “functional economic areas”, which is a term used to describe travel-to-work, travel-to-retail or housing market areas, particularly around major metropolitan centres. In the case of the NECA deal, however, some participants questioned the extent to which this model applied. It was argued that the NECA area could certainly not be regarded as a coherent city-region like the West Midlands or Greater Manchester. NECA covers the Tyne & Wear urban region (itself containing the two separate cities of Newcastle and Sunderland – areas 2a and 2e) as well as large rural and coastal areas stretching up to the Scottish border and down to the Tees Valley.

Speakers described the region as ‘polycentric’ and also as ‘linear’, with economic activity and the population stretching along the A1 and East Coast mainline. One speaker wondered whether much of the turmoil over devolution in this region could have been avoided by retaining (or perhaps even recreating) the old Tyne & Wear metropolitan county council (area 2), which was abolished in 1986 leaving a legacy including the Metro urban rail system that connects Newcastle, Gateshead and Sunderland.

The mayoral model

A common criticism of the government’s approach to devolution concerned its insistence on the introduction of elected mayors spanning multiple local areas. One participant argued that the mayoral model had been designed with contiguous metropolitan regions such as Greater London and Greater Manchester in mind and then rolled out to very different places where it didn’t fit.

In Tees Valley, where the devolution deal is going ahead, a speaker argued that the metro mayor model may be more suitable, since the five local areas function more like an integrated city region around the urban centre of Middlesbrough. Nonetheless, here too there was little actual enthusiasm for the mayoral model, which central government was perceived to favour to ensure there was a single point of contact for them to deal with.

One speaker suggested that the local councils in question had not fully realised they were locked in to a mayoral model until too late, and that there had then been attempts to draft the terms of the devolution deal to tie the hands of the new mayor as far as possible. This is worrying, since for the Tees Valley deal (and any potential future Greater Newcastle deal) to work, the new metro mayors will have to form effective working relationships with the leaders of the councils across their region, who will sit on a leadership group chaired by the mayor as well as scrutinising mayoral spending plans and other decisions.

A further layer of complexity derives from the police areas, which do not align with the geography of the devolution deals. There are three police forces in the North East: Northumbria (covering areas 1 and 2), Durham (areas 3 and 4), and Cleveland (areas 5-8). Durham therefore spans the NECA and Tees Valley areas. Again this contrasts with London and Manchester, where there is a single police area that aligns with the geography of the wider city region. This fact made it easier for the London Mayor to take on responsibility for the Metropolitan Police in 2012. In Greater Manchester, the new mayor will likewise absorb the Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) functions from May 2017. This will not happen in the north east, where directly elected PCCs will continue to exist alongside the new Tees Valley mayor and whatever emerges in and around Newcastle.

Money troubles

Money was also on the minds of many. One speaker identified the loss of EU structural funds as a result of Brexit as a key factor contributing to the rejection of the NECA deal, especially since the vote to leave the EU follows several years of tight spending settlements for local government across the country. The additional monies promised by central government for infrastructure investment – £30m and £15m per year for 30 years the NECA and Tees Valley deals respectively – were also seen as insufficient. One speaker referred to the sum on offer as “a joke”.

Another question posed was how the government could guarantee extra funding for three decades – this was seen as a meaningless pledge since the political and fiscal context even three years hence cannot be predicted. The concern was that councils would find their budgets squeezed after having taken on additional spending responsibilities. In Tees Valley, it was suggested, the deal had passed despite, not because of, the extra money on offer. The big win was seen as the greater freedoms to join up budgetary and policy decisions that were currently siloed – for instance, ensuring that suitable transport infrastructure was created to meet the needs of new businesses investing in the region.

The planned devolution of business rate revenue was also viewed warily. The proposed model will see revenue from non-domestic rates paid by medium and large companies retained by councils rather than being hoovered up and dished back out again by Whitehall. The full details of how this will work have yet to be confirmed, but the new system is expected to entail less redistribution than at present from richer to poorer areas.

Even in relatively economically successful parts of the north east, there appeared to be concern about the perverse incentives this reform would introduce, pushing local authorities to prioritise the building of large shopping centres and distribution centres, rather than encouraging the development of housing or small business. A further concern was that smaller authorities might be left highly dependent on one or two large local employers, who might choose to relocate at any time, leaving a hole in the budget that councils have little ability to fill.

The overall mood in the room was of cautious support for the principle of devolution and greater local decision-making combined with scepticism and concern about precisely how the devolution process was unfolding. Combined with the apparent ‘deprioritisation’ of devolution by the new UK government since the summer, one has to wonder whether this agenda is, once again, in danger of running out of momentum completely.

Map of the North East Region

Key: 1. Northumberland (county council); 2. Tyne and Wear metropolitan county, comprising – a. Newcastle Upon Tyne, b. Gateshead, c. North Tyneside, d. South Tyneside, e. Sunderland; 3. County Durham (county council); 4. Darlington; 5. Hartlepool; 6. Stockton-on-Tees; Redcar and Cleveland; 8. Middlesborough.

Map source: Dr Greg and Nilfanion. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2011 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ANorth_East_England_counties_2009_map.svg

Akash Paun is a Fellow of @instituteforgov, leading work on devolution. He is an expert adviser to British Academy's Governing England project.