The pomp, strategy and betrayal of the first Franco-Russian summit

by Professor William Doyle

23 May 2018

The first Franco-Russian summit took place between 25 June and 9 July, 1807. Rare enough even today, face-to-face meetings between heads of state were almost unknown in early modern times. Rulers normally communicated, even on paper, through their ministers. But Emperor Napoleon I, who had ruled France since 1799, and Tsar Alexander I, who had come to power in Russia two years later, were fascinated to meet one another.

Napoleon in the ascendency

France and Russia had been at war since the summer of 1805, and Napoleon had had the best of it. Alexander had witnessed the destruction of an Austro-Russian army in 1805 at Austerlitz, which was perhaps Napoleon’s most brilliant victory. Russia fought on without Austria, but Napoleon soon defeated a second Russian ally, Prussia, at Jena-Auerstadt in 1806, and pushed on eastwards to threaten a Russian empire not invaded by foreign armies for a century.

He was stopped in February the next year at the bloody midwinter battle of Eylau, which he claimed to have won, despite the Russians withdrawing in good order. But five months later he scored a decisive victory at Friedland – Prussian territory – and Alexander at once sued for an armistice. Napoleon welcomed the approach. Although victorious, he was far from his home base and was ill-equipped to push further east.

Pomp, strategy and charm offensives

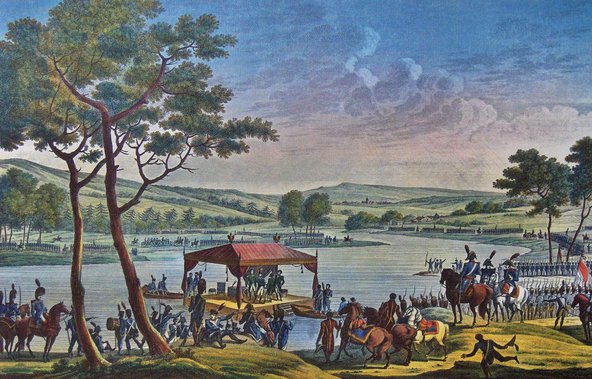

The two rulers met to settle peace terms at Tilsit on the river Niemen, the frontier between Russia and Prussia. Neutral ground was created by a raft moored in mid-stream. And here they set about dividing spheres of influence in Europe between them.

Coloured litho by Carle Vernet depicting the meeting between Emperor Napoleon I and Tsar Alexander I on the River Niemen. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Negotiations took place in surroundings of great pomp and military display on both sides as both tried to impress the other, and the two rulers spent many hours alone together. Napoleon was quite impressed by the only European ruler younger than himself, partly perhaps because the Tsar was obviously in awe of him. Indeed, Alexander was so taken with the Napoleon that Russian diplomats believed their leader had given away too much to one of Napoleon’s notorious charm offensives, and dreaded them ever meeting again. But Alexander had lost the war, and so had little alternative to making concessions to French demands.

Carving up Europe, establishing the Duchy of Warsaw and strangling Great Britain

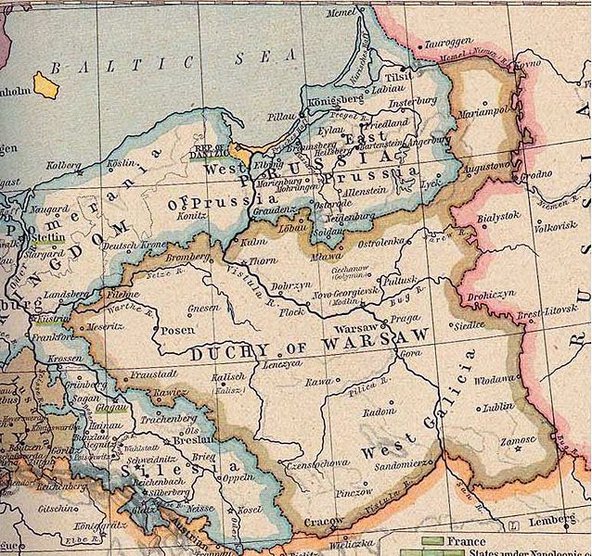

Russia’s only precondition was that she would surrender no territory. In return, she recognised all France’s gains in the west since 1805, such as France’s Rhine frontier and the complete reorganisation of Germany. She also agreed to the partial dismemberment of her Prussian ally’s territory. Most importantly, this involved the re-creation of a Polish state, which had not existed since the eastern powers had partitioned the old kingdom between them in 1795. It was not called Poland, but rather the Duchy of Warsaw, but its establishment won Napoleon the everlasting gratitude of Poles, many of whom fought enthusiastically in his armies until the bitter end.

Alexander was uneasy, as Russians still are, at the prospect of independent states on his country's western borders

Alexander was uneasy, as Russians still are, at the prospect of independent states on his country's western borders. He saw at once that the new Duchy would be a French puppet, and was uncomfortably aware that his own realms included many potentially restless Polish subjects absorbed into Russia through the partition. But he hoped Napoleon would exercise restraint in gratitude for his agreement to concert action against Great Britain. Russia and Britain had been allies against France in the war, but Alexander felt that he had been repeatedly let down, if not betrayed, by the notoriously perfidious British. He now, he told Napoleon, hated the British as much as he did. He undertook to exclude Britain from the Baltic and Russian trade, thereby complementing Napoleon’s ‘continental system’ of strangling Britain through a commercial boycott.

By establishing the Duchy of Warsaw, Napoleon weakened Prussia, increased his power in the region and won the everlasting gratitude of Poles. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Britain now seemed completely isolated, and two great and mutually invincible empires had seemingly divided European hegemony between them. But the British always found ways around the continental system, and Alexander discovered, like others before him, that no deal struck with Napoleon could ever be relied on.

Betrayal, empty promises and victory

Soon the French emperor was obstructing Russian interests in the Balkans, strengthening the Duchy of Warsaw, and extending his own power into Iberia. At a second meeting between Napoleon and Alexander at Erfurt in 1808, to which in effect Napoleon had summoned the Tsar like a dependent, Alexander was far from cowed. He agreed not to obstruct French policy in Spain, but came away proud to have made nothing more than empty promises.

Mutual mistrust was now firmly established, and over the next three years Napoleon came to see Russia more as a rival than a pliant partner. By 1811 he was clearly planning a military campaign to reinforce the lessons of Austerlitz, Eylau and Friedland that French arms were invincible. The Russians never accepted this, and proved they were right when Napoleon finally, and fatefully, invaded their territory in 1812 with what was then the largest army ever assembled in the history of warfare – numbering 680,000.

Once again Napoleon came to see Russia more as a rival than a pliant partner

To Napoleon's fury, the Russians refused to negotiate even when he reached Moscow. The city was deserted and burning, the Russians having employed scorched earth tactics as they retreated. Unable to find supplies – or indeed an army to fight – Napoleon was eventually forced to retreat in the depth of the Russian winter. With temperatures as low as -24 degrees Celsius, many of Napoleon’s soldiers and horses froze to death, and many more deserted.

Painting by Viktor Mazurovsky depicting Napoleon's retreat from Moscow in 1812. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Napoleon’s fortunes never really recovered, and in 1814 Alexander marched into Paris as Napoleon abdicated. Tilsit was undone. France was reduced to its pre-Napoleonic size. Prussian power was restored, and all that remained of Tilsit was a re-created Poland, but this time completely under Russian – rather than French – domination, with Alexander as its king.

William Doyle FBA is Professor of History at Bristol University. He specialises in 18th-century France and is one of the leading revisionist historians of the French Revolution, obtaining his doctorate from the University of Oxford with a thesis entitled The Parlementaires of Bordeaux at the End of the Eighteenth Century, 1775-1790. He is the author of, among other titles, the Oxford History of the French Revolution (1989), The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction (2001), and Aristocracy and Its Enemies in the Age of Revolution (2009).