Few people have escaped conversations about the limitations of online communication and how much face-to-face meetings and physical contact have been missed during lockdown. Yet many would also be utterly aghast at the very idea of facing lockdown and social isolation without smartphones and online conversation. In many instances, including changes to academic and work practices, there is a feeling that COVID-19 has made a trajectory towards online more precipitous, but that this was anyway the direction of travel.

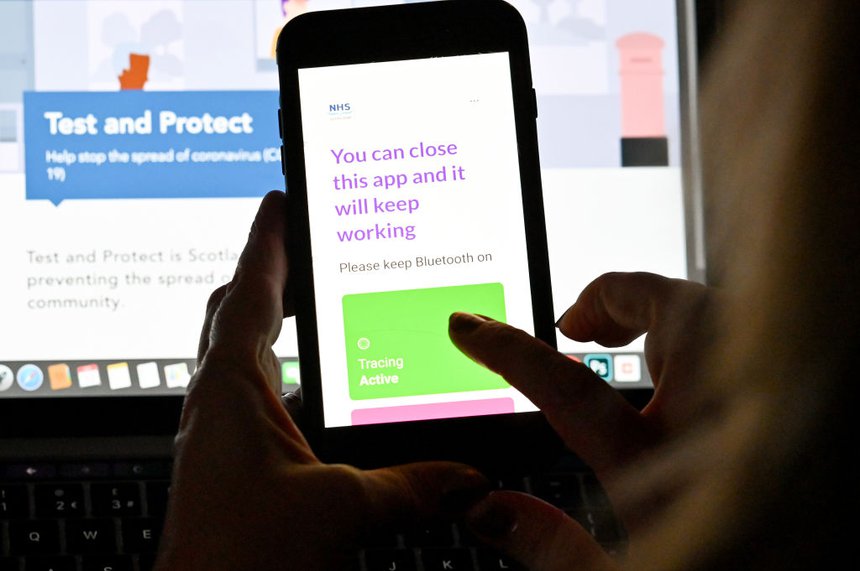

Smartphones have also been central to the response to the pandemic, as seen in the development of track-and-trace apps. This is a technological development, but the effect has varied hugely across the world. The reason is that track-and-trace has exposed the considerable potential of smartphones for surveillance, but also as a technology of care. Deciding the balance between surveillance and care is a moral, not a technological question. The heterogeneity of response merely reflects the fact that the population of South Korea and US Republicans, to take two examples, are unlikely to agree on whether to prioritise the health concerns of the state or the privacy of individuals.

As it happens, just before the pandemic a project called The Anthropology of Smartphones and Smart Ageing (ASSA) was drawing up its conclusions from ten simultaneous 16-month ethnographies carried out across the globe. One of these conclusions was precisely that ‘there is a fine line between care and surveillance’. We had been working mainly with people in middle-age, many of whom were looking after elderly parents. The spread of smartphones to older people is very recent, yet already it seems like an automatic response, when a parent becomes frail, to create a WhatsApp group of siblings to help organise their care. However, whether one is in Japan or Brazil, there are issues around one’s parent’s dignity and autonomy that are central to the sensitivity of such care.

The diversity of online communications

Two things seemed clear. The first is the need to prioritise research on the impact of online – whether the ubiquity of smartphones, the rise of social media or these changes in the context of work. But the second seemed to be the necessity of anthropology. There are two main reasons for the latter. The first was our evidence that these technologies express heterogeneity rather than create homogeneity. One reason is that the smartphone is built for subsequent adaptation by its user. To even find out what a smartphone is in each context required asking individuals to open up their handsets and then go through them app by app, collecting stories and observing how each app was used in everyday life, often in surprising combinations. There is no standard smartphone; they quickly become highly expressive of the interests and needs of each individual.

The ASSA project followed on from the prior Why We Post project, which focused on social media use in nine different countries. Again, the result was extraordinary diversity. A comparative study in El Mirador, Trinidad and the Glades, England observed differences in social media behaviours of new mothers. In the Glades, new mothers typically adjusted to posting predominantly about their child, who typically for a while replace the mother as her profile picture, whereas in El Mirador, they typically continue to show their individual style and personality through their posts. The Why We Post project also highlighted how, in some regions, social media is seen as the death of privacy, while in our field sites in China and India, for people in extended family households, social networking expanded the possibilities of privacy. Low-income people in a village in Northeast Brazil were posting their aspirations for upward social mobility, posing against backgrounds such as swimming pools, while a similar low-income population in Alto Hospicio, Chile assumed that since their friends on Facebook knew each other, they could not post anything that others would know was not true of their actual lives.

Policy and Research

COVID-19 – Shape the Future

How to create a positive post-pandemic future for people, the economy and the environment.

An equally important argument for the necessity of ethnography was that most postings are not about politics on Twitter, but private family correspondence on different messaging apps, such as LINE in Japan, WeChat in China and WhatsApp in most other areas. Unless one spends months establishing trust, it is impossible to directly observe the heart of what social media and smartphones are actually used for. This hugely important transformation in the world is, in practice, not at all amenable to scholarly research, but it is increasingly important to education that we know what is going on from direct observation, rather than self-reported information.

Fortunately, the same approach to contextualised research has helped, in turn, with the dissemination of results. By using Open-Access publication models, social media, a free MOOC and constantly blogging about our findings and fieldwork, it is possible to reach out and contribute to education across the globe. The Why We Post project was published in 11 volumes by UCL Press and downloads recently passed one million worldwide.

Digital media for health

One of the findings of the ASSA project concerns the use of digital media for health. Most research around the topic of mobile health is directed at the huge commercial potential of mHealth bespoke smartphone apps developed for health purposes, but our ethnographic projects found that it is the use of everyday apps such as Google, YouTube and WhatsApp that have by far the most important consequences for health. We therefore concentrated on studying how people are employing these ubiquitous apps in relation to health and welfare.

Much of this can be summarised as a significant transformation in our contemporary world. The word ‘smart’ used in the context of smartphones and ‘smart cities’ concerns machines with the capacity for autonomous learning. Attention is focused on algorithms and Artificial Intelligence and the equal sense of promise and threat that these imply for our future. But perhaps even more important is the rise of what we call ‘smart from below’. What we actually encounter as smartphones and social media represents a vast opening up to the creation of content by ordinary people, in diverse ways that reflect mainly local cultural values. This is what is keeping us digital anthropologists very busy indeed.

Daniel Miller is Professor of Anthropology at University College London. He was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 2008. He currently directs the ‘Anthropology of Smartphones and Smart Ageing (ASSA)’ project and previously directed the ‘Why We Post’ project.