How did cults of saints spread across the medieval Christian world?

by Dr Johanna Dale

3 Jun 2020

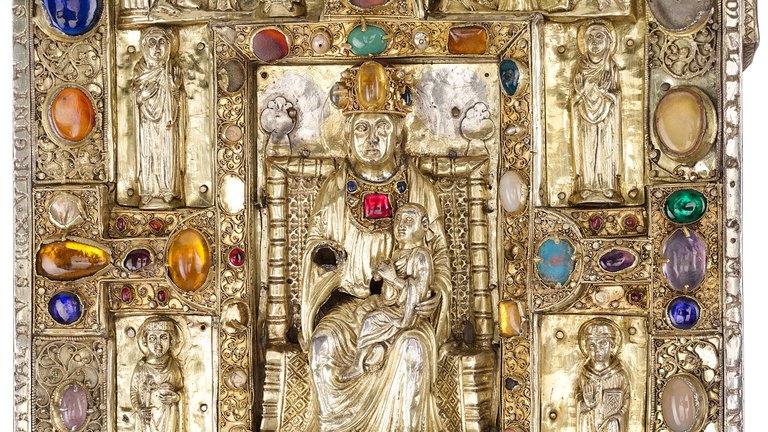

Why was a Northumbrian king, who had been killed in battle in 642, depicted on the jewelled cover of a religious book produced in southern Germany over five centuries later in 1215-17? How could this king, considered in high-medieval England to be the epitome of early medieval Christian kingship, be upstaged by a talking raven (with a tendency to sulk when hungry) in medieval German vernacular legends? Why are a handful of villages in the German-speaking Alps named after Oswald? These are some of the questions my project seeks to answer, in order to better understand the dynamics of cultural change and exchange in high medieval Europe.

The role of saints in the medieval Christian world

Veneration of the saints was a central plank of medieval Christianity. However, not all saints were equally important. Some saints had pretty much universal appeal and were venerated across the Christian world. Saints in this category tended to have been established very early. They were often biblical figures, eg John the Baptist, the Disciples and Evangelists, or victims of Roman persecution, eg Lawrence.

At the other end of the scale were saints with purely local cults. Peterborough Abbey, for example, had an altar and chapel dedicated to three seventh-century women: Kyneburga, Kyneswide and Tibba. All three had been abbesses at the nearby monastery at Castor. They were also members of the Mercian royal family, who were the original founders of the monastery at Peterborough. Surviving liturgical evidence, such as calendars, musical books and the directions for the celebration of saints’ feast days, suggests these three women were important to Peterborough and the surrounding Fenlands throughout the Middle Ages, but that outside of their home region, there was little interest in them.

Just along from their chapel in the south transept at Peterborough was a chapel dedicated to Oswald of Northumbria. Oswald had died in battle fighting the Mercian ruler Penda in 642, so as well as having no particular historical or geographical relevance, he had a rather awkward relationship to the abbey’s founding family. In spite of this, Oswald was of huge importance to the community. This was because the monks had acquired, in very dubious circumstances, the most famous relic associated with the saint-king: his incorrupt right arm.

Originally in the possession of St Peter’s Church at Bamburgh, in Oswald’s native Northumbria, the arm was brought to Peterborough by a monk named Winegot some time before the Norman Conquest – a high-profile case of the relatively widespread phenomenon of relic theft.

The cult of Oswald

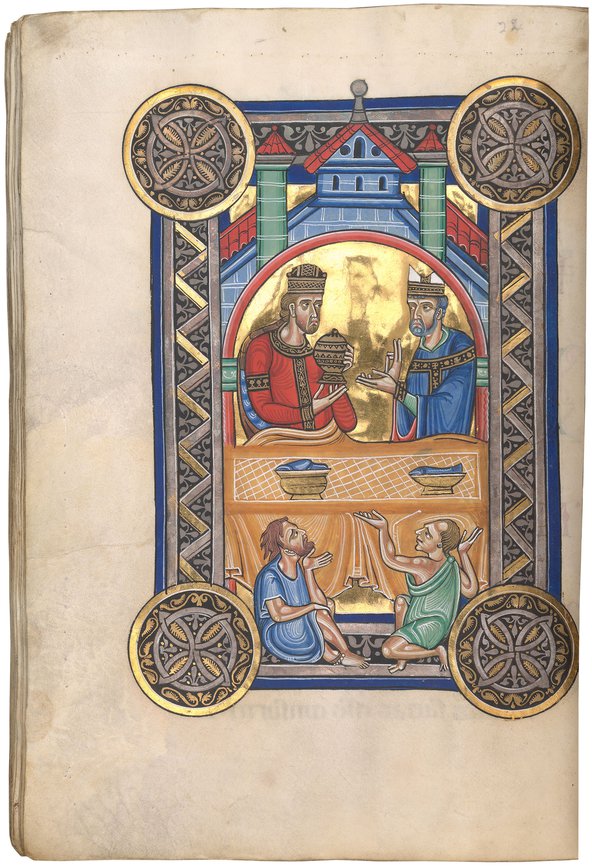

By the time Peterborough acquired the arm, Oswald was already venerated widely in England. He was invoked for the king in the laudes regiae, a liturgical acclamation used at coronations, and his feast day, 5 August, is found in calendars from across the British Isles.

The monks at Peterborough thus drew on existing traditions when they commemorated Oswald, but through their nurturing of the cult they also, over time, adapted traditions to fit their circumstances, interests and aspirations. It is these changes and the knock-on effects they have that particularly interest me, because they can help us to understand wider processes of cultural change and exchange.

Material and textual evidence from Peterborough points to the existence of a highly developed liturgical cult surrounding Oswald’s arm relic. The great 12th-century chronicler of the abbey, a monk named Hugh Candidus, records several occasions on which the arm was removed from its reliquary so that people could admire the uncorrupted flesh and also recounts an event at which the bishop of Lincoln used the arm reliquary to bless the congregation. Unfortunately the reliquary does not survive, but we know that in the early 13th century Abbot Acharius had given a case of gold and silver set with precious stones to protect the arm – and that in 1515 a monk, John Walpole, was disciplined by the bishop for stealing jewels from the shrine and giving them to townswomen.

Cultural exchange through liturgy

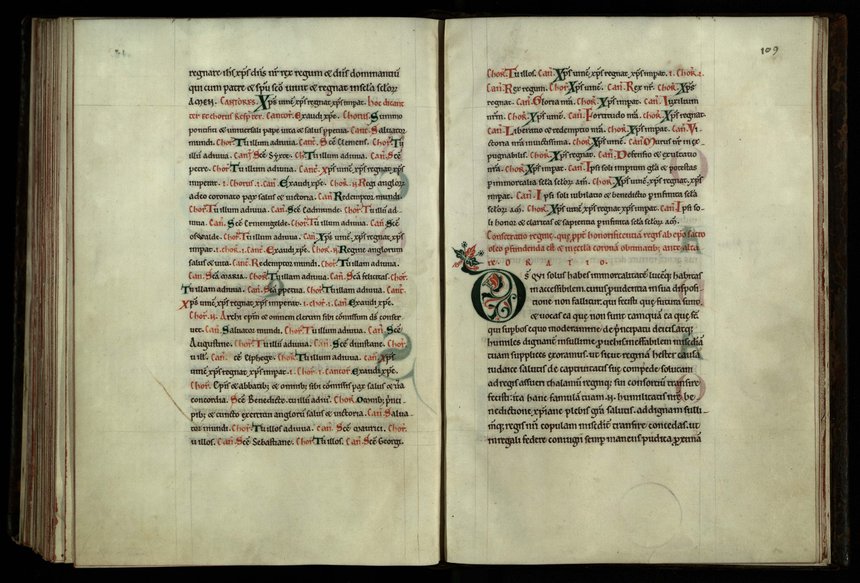

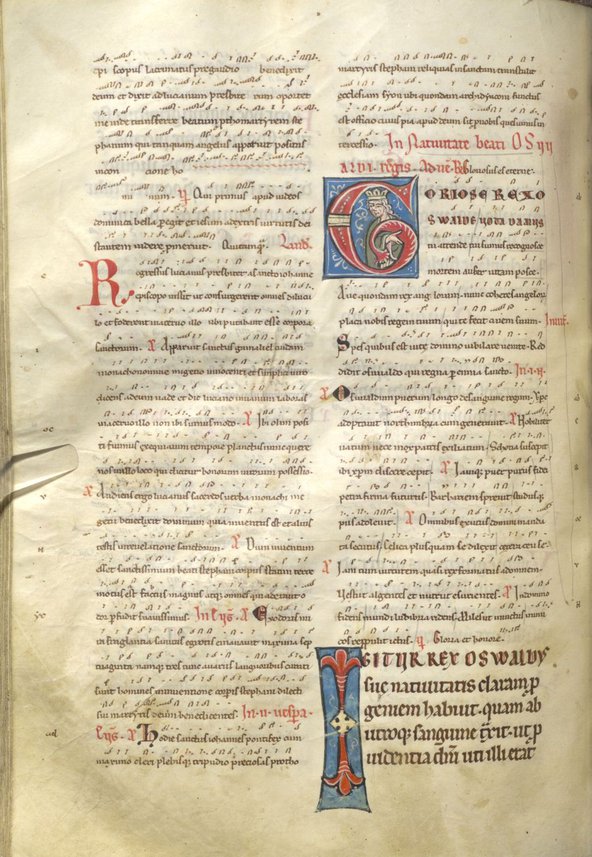

Two manuscripts surviving from medieval Peterborough show how the monks adapted and elaborated the liturgy for Oswald’s office, the prayers, chants and readings for the celebration of his feast day. Annotations in an 11th-century copy of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History demonstrate that the monks chose readings for the feast day, which had special resonances for the community. The complete chant cycle for Oswald’s feast day, surviving in a 14th-century antiphoner (a book containing musical chants), demonstrates how the monks elaborated the existing ‘English’ office for Oswald by importing chants from an independent ‘continental’ office, which survives in eight medieval manuscripts, one from Flanders and the rest from German-speaking lands. It’s unclear through which connections the ‘continental’ chants came to be inserted in Oswald’s office at Peterborough, but the partial amalgamation of the two shows both the extent to which the abbey was firmly embedded in wider networks of veneration, and also the centrality of the liturgy to cultural change and exchange.

By placing the liturgy at the centre of my research, I hope one day to be able to explain Oswald's metamorphosis from the austere and pious king depicted in Latin and Old English sources, to the legendary figure found in German vernacular texts. While Oswald’s talking raven, who journeys to the east to seek a bride for his master, encountering mermaids and a golden stag on the way, seems very far removed from traditional religious practices, those very practices provide the key to understanding how such a pronounced change could happen.

Dr Johanna Dale is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at University College London studying History, Literature, Liturgy and Identity in the European Middle Ages. Her research on St Oswald featured in the British Academy Virtual Summer Showcase.

Lead image: the jewelled cover of the Berthold Sacramentary, Weingarten, Germany, 1215-17 (The Morgan Library, New York, MS M.710)