Who hasn’t bounced back? Well-being and the recession

by Dr Lindsay Richards

22 Jan 2015

Think about a positive event you’ve experienced like getting a new job or a pay rise, embarking on a new romantic relationship or even winning £10 on a scratch card, and think how you felt… and then try to remember how long it was before the positive emotions began to wear off and you settled back into normal. A famous study in the 1970s compared the happiness of lottery winners and accident victims to a control group and found that the lottery winners were no happier than ‘normal’ people. Not only were the lottery winners less happy than some might have expected, but they rated everyday experiences like eating and spending time with friends as less pleasurable than everyone else. The authors labelled the phenomenon ‘habituation’ – basically, given enough time, we get used to anything and we adjust our preferences in accordance with life circumstances. That’s the theory anyway.

A connected idea is that of the happiness ‘set-point’ which is a predetermined level of happiness (largely influenced by genetics) to which we’ll bounce back after positive events like getting married, and from negative events like getting divorced. Some research (though not everyone agrees) suggests that there are no lingering effects on happiness at all from life events that happened more than six months ago.

But what about the great recession? Have we all bounced back from that as well? The truth is that some measurements show that the recession had no impact at all on our happiness, not even a blip. How is this possible? We’ve all seen the news and know that wages have stagnated while prices have continued to rise, that unemployment started to rise in 2008 and is still not back to pre-recession levels, and that ‘austerity measures’ mean that economic hardship is being felt disproportionately by the most vulnerable in society.

Set-point theory and flat-lining satisfaction might suggest that nothing influences our happiness and that we just carry on regardless whatever is going on around us. It could suggest that goals are pointless and the economy of the country doesn’t matter. This conclusion would be a mistake.

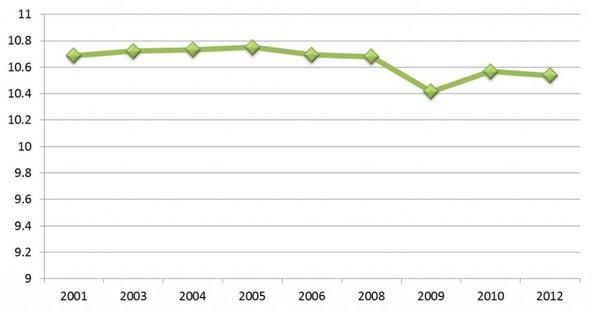

What’s going on? Two things. Firstly, we need to get the measurement right. What do we mean when we say ‘well-being’ or ‘happiness’? Many academic researchers are interested in life satisfaction, which is an evaluation of how we feel about our lives when we stop and think about it. This is in contrast to life as we experience it, or to more direct measures of our mental health. To illustrate we looked at a measure of psychological well-being where people were asked several questions about whether they have recently been losing sleep, worrying, or felt under strain. Unlike the measures of satisfaction, here we do see a reduction in the psychological well-being score in 2009 which then seems to, more or less, bounce back (fig 1).

Fig 1 – Psychological well-being between 2001 and 2012

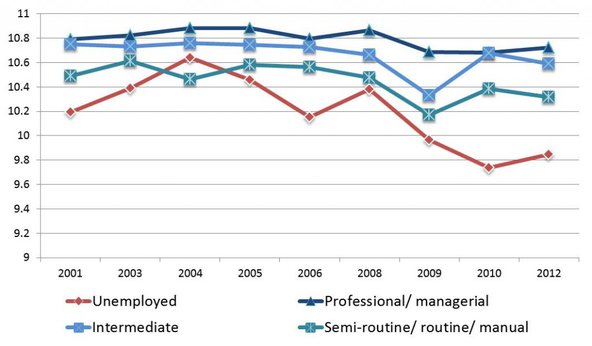

What about the casualties of the recession? And this is the second thing we need to get right. If we think that the shocks to our economy disproportionately affect the vulnerable, then we should look at the well-being of these groups rather than country-level averages. When we compare across occupational classes, for example, we can see that people in intermediate and routine occupations took a bigger hit to their psychological well-being than professionals did (fig 2). And while the intermediate class bounced back completely, the routine class didn’t quite reach their pre-recession levels. And how did the unemployed fare? Their psychological well-being took a dive and is still well below the pre-recession level. This suggests that the social safety net is not doing its job.

Fig 2 – Psychological well-being by occupational class/ unemployment

To come back to habituation and set-points; the recession has not been ‘habituated’ but has had real lasting costs to the psychological well-being of those at the receiving end of economic recession such as the unemployed, and to a lesser degree those in routine occupations. And thinking back to that original 1970s study, well, the accident victims were less happy than the control group, a point that often gets forgotten in discussions about the study. Among other exceptions to set-point theory is research showing that, unsurprisingly, people don’t adapt to poverty and infringements of their human rights.

So, what does this all mean? I think it means that if we are going to bring about greater happiness in society, and to capitalise on the government’s National Well-Being initiative, we need to focus on long-lasting ‘states’ of low well-being. Do subjective measures have a value? It could be dangerous to depend on subjective measures entirely, but they may have an important role to play in highlighting inequalities in how life is experienced. However, to get a true picture of subjective well-being in our society we should follow the golden rules: look at more than one measure and compare outcomes for different groups of people.

Lindsay Richards is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College, Oxford.