Burnt books: The British Academy and the restoration of two academic libraries

- Date

- 15 Jan 2017

Published in British Academy Review, No. 29 (January 2017).

The print version of this article can be downloaded as a PDF file.

Louvain

Early in the First World War, on 25 August 1914, the German army set fire to the Belgian city of Louvain. The burning and looting lasted for five days, and Louvain’s ancient library was destroyed.

At a meeting on 10 March 1915, the British Academy’s President, Lord Reay ‘submitted to the Council [of the British Academy] certain preliminary proposals received by him from the Institut de France with reference to the formation of an International Committee for collecting books and gifts for a new Library for the University of Louvain; Lord Reay explained that the idea was that the British Academy should help the proposal by means of a Special Committee, and by delegating Representatives to serve on the International Committee.’ The Academy’s Council responded positively – though at the same time they ‘wished to emphasise their opinion that the project should not be allowed to weaken in any way the responsibility of the Germans in respect of the destruction of the Library’ [note 1].

At its meeting on 3 June 1915, the Council again discussed the Louvain Library ‘movement’, and resolved ‘that a British Committee be formed to consist of the aforementioned Fellows with power to add to their number other Fellows of the Academy, together with representatives of the Universities, the Royal and other learned Societies, such other institutions as may be asked to send delegates to serve on the Committee, to which Committee other distinguished persons might be added.’ The list of seven ‘aforementioned’ Fellows of the British Academy included two members of Asquith’s new coalition government – Mr Arthur Balfour and Lord Curzon [note 2].

Inevitably, the restoration of the library at Louvain would have to wait until the end of the war, when the Germans would no longer be occupying the city.

Tokyo

Just a few years later, on the other side of the world, a natural disaster destroyed another library. On 1 September 1923 at 11.58am, an earthquake of magnitude 7.9 devastated Tokyo. The earthquake hit just as people were preparing their lunch and, in a city largely made of wood, it was fire that caused the greatest amount of damage and loss of life. At Tokyo Imperial University, 700,000 library books went up in flames.

On 20 October 1923, Lord Curzon FBA, who was now Britain’s Foreign Secretary, wrote to (now) Lord Balfour FBA, who had become President of the British Academy. ‘The Foreign Office have just received through our Embassy at Tokyo an appeal from Tokyo Imperial University for books to restore their library, which was destroyed by fire at the time of the recent earthquake. I am writing to you as President of the British Academy to enquire whether anything can be done on a national or possibly international basis to help the Tokyo University, on lines similar to those adopted in the case of Louvain.’ Curzon recalled that both he and Balfour had served on the Louvain committee set up by the British Academy. Curzon went on to explain the Foreign Office’s motivations. ‘The appeal of the Imperial University, which is the training-ground of almost all the future officials of the Japanese Government, offers an opportunity to provide a permanent evidence of our feelings; and our assistance in this direction would be greatly appreciated in Japan – a country where education commands so much attention. I hope therefore that the British Academy may find it possible to interest itself in this proposal.’

On 24 October, Balfour reported to the Secretary of the British Academy, Sir Israel Gollancz, that he had been approached in this way by Curzon. ‘I have replied that I would at once do all that I could to help the Foreign Office to carry out his plan.’ His memory of the Louvain example was clearly less sharp than Curzon’s: ‘Though I appear to have been mixed up in the Louvain scheme, I have very little recollection of it; but I have no doubt that Lord Curzon is right in thinking that that is the precedent that ought to be followed.’ [note 3]

Once fired up, Balfour grasped the need to co-ordinate the British efforts to rebuild the library in Tokyo. Without ‘some effective attempt to organize the work of restoration,’ he wrote, ‘confusion and duplication will inevitably occur; much will be left undone that might have been done; and much will be done twice over. In these circumstances I propose, as President of the British Academy, to bring forward at the next meeting of the Council [on 5 December 1923] a formal resolution to the effect that a representative Committee be appointed to deal with the problem as a whole. This was the course adopted in 1915 in the case of the Library of Louvain; and the plan seems to have worked satisfactorily.’ [note 4]

On 10 December 1923, the British Academy hosted a ‘General Meeting’ of representatives of learned societies and selected scholars to discuss the matter. That meeting endorsed the proposal that a co-operative effort should be made to restore the English section of the Tokyo Imperial University Library, and appointed an Executive Committee to move things forward.

From the outset, the Foreign Office recognised that the library could not be restored through donations alone. On 2 August 1924, Prime Minister Ramsay Macdonald wrote to the Japanese Ambassador to report that the Government was ‘anxious to give practical support to the work undertaken by the British Academy in collecting books in this country to supply the University’s needs’, and that Parliament had voted the sum of £25,000 for the purchase of books. ‘It is proposed to spend this sum in consultation with the British Academy Committee, which is already, I understand, in close relations with you’ [note 6].

Israel Gollancz took on responsibility for co-ordinating the lists of books being donated and bought for the Tokyo Imperial University Library. In this he was ably assisted first by Miss E.M. Pool, and then by Miss D.W. Pearson. After graduating from King’s College London in 1922 where she had been tutored by Gollancz, Doris Pearson had spent a few years teaching before applying to assist Gollancz with the Tokyo book project in January 1926; ‘Well,’ said Sir Israel at the end of the interview, ‘I have also asked people trained in librarianship to come along to see me, but I am going to offer this post to you.’ [note 7] And so began Doris’s long career at the British Academy – she was the sole paid member of staff until 1949, and retired in 1970 after 44 years of service.

Notes

1. Incidents from the sack of Louvain by the Germans would feature in the Report of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages, which was published in May 1915. At the time, this Government-commissioned report constituted something of a propaganda coup for the British. The Committee was chaired by Viscount Bryce, President of the British Academy; other members included Sir Frederick Pollock FBA and H.A.L. Fisher FBA.

2. Both Arthur Balfour and George Nathaniel Curzon were Founding Fellows of the British Academy when it was established in 1902. Balfour was Prime Minister 1902–1905, and later as Foreign Secretary he was author of the ‘Balfour Declaration’ in 1917.

3. Curzon and Balfour letters, BAA/GOV/2/2/5.

4. Quoted in ‘Report on the British Gift of Books to the Tokyo Imperial University Library’, BA465.

5. See ‘Charles Wakefield and the British Academy’s first home’, British Academy Review, 21 (January 2013), 64–6.

6. Quoted in ‘Report on the British Gift of Books’.

7. Autobiographical note, BA416.

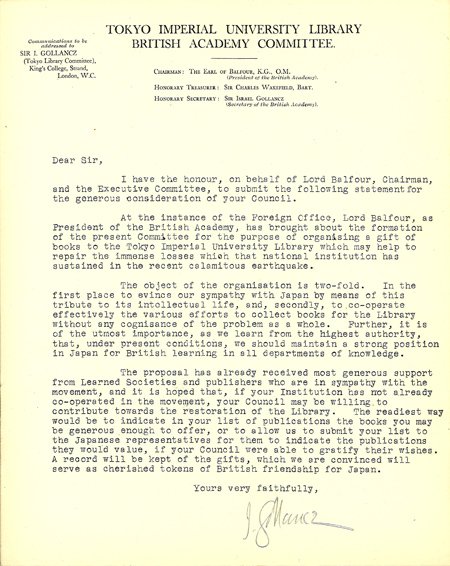

Illustration: Letter from Sir Israel Gollancz FBA, Honorary Secretary of the Tokyo Imperial University Library British Academy Committee, sent in March 1924 to the Councils of various learned societies, asking for contributions of books to help restore the destroyed library. BA457.