How governments use psy-technology to influence people’s behaviour

by Dr China Mills and Dr Elise Klein

4 Jul 2018

Changing people’s behaviour has long been an aim of governments around the world. It is now being named explicitly as a key frontier in international development policy, delivered by state and non-state actors. Technology plays a key part in behaviour change: smartphones and algorithms nudge behavioural changes; income management regimes and debit cards shape spending; technology aids mental health diagnoses and clinical management; and apps are designed to increase resilience or reduce stress.

In parts of the global North, the growing influence of digital or psy-technology is often framed as evidence of the emergence of individual ‘quantified selves’ who are living an ‘algorithmic life’. Many are optimistic about technology, claiming it can enable empowerment, especially in relation to health and development. Others are more critical and instead focus, for example, on the ways technologies can be enforced and used for surveillance or governance. In our research, we’re interested in both these perspectives but also in the in-between spaces – the ways technologies are used creatively, appropriated, resisted or refused.

Our research analyses the ‘social life’ of digital technologies for behaviour change in India, South Africa and Australia. By ‘social life’ we mean the production, use, appropriation and resistance of specific technologies, and their impact on self- and health-making. Here we’ll focus on two examples: the use of digital technology to manage stress in India; and trials in Australia of the Cashless Debit Card.

Changing behaviour through technology

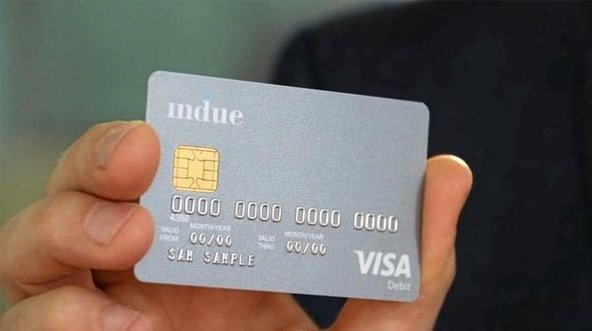

In Australia, the Federal government have disproportionately targeted First Nations people with the top-down implementation of the Cashless Debit Card. The card automatically quarantines 80% of a person’s welfare benefits and restricts purchases with the aim of promoting “socially responsible behaviour”.

Assumed alcoholism amongst indigenous Australians and unemployment are the main framing devices of the ‘problem’, to which income management is positioned as the ‘solution’. The card’s logic is based on a distorted perception that alcohol, drug use and gambling are the primary causes of poverty. Interestingly, most people forcibly put on the card – and their families – do not gamble or report consuming illegal drugs or alcohol in excess. Instead, the trial has exacerbated economic insecurity for poor families by limiting the cash they have to pay for informal renting arrangements, second-hand goods, cash purchases of locally grown produce, and pocket money for children.

Both the Cashless Debit Card in Australia, and the No More Tension app and stress calculator in India, frame certain behaviours as problematic in particular ways. The app establishes certain affective experiences as ‘stress’, while the card frames unemployment and certain kinds of consumption, particularly of and by First Nations people, as problematic. These behaviours not only become ‘problems’ but also individual problems, that assume individual lifestyle change, voluntary or enforced, is the solution.

Monitoring individual behaviour

In India, the No More Tension app incites individuals to voluntarily use the app to manage their own lifestyle and reduce their stress levels. The online stress calculator and app show a governmental preoccupation with stress and tension, which is seen as manageable through individuals’ engagement with technology. Conversely, the Cashless Debit Card is imposed top-down: the state assumes responsibility for enforcing behaviour change, assuming that First Nations Australians cannot or will not change behaviours that the state has deemed problematic. What these technologies have in common is that neither focus on the underlying, structural reasons for rising stress levels or alcohol consumption.

The different technologies make different assumptions around individual decision-making and responsibility. Digitisation is not always or only a one-directional export of ‘Western’ technology onto a ‘passive’ population. Technology mediates the connection between local and global public health agendas in new ways that govern and discipline, as well as in ways that liberate and empower. In India, self-management apps exist alongside more development-focused technologies, such as the training of community health workers to administer digital tools for the diagnosis and management of mental health issues. The use of mental health diagnostic algorithms, such as the WHO’s mhGAP-Intervention Guide and app (currently being trialled in India), are a good example of this. These tools are explicitly designed to impact on clinical decision-making and move diagnostic decision-making out of the psychiatric clinic, onto community health workers in low and middle-income contexts. This is part of a general trend in India, where much mental health technology is designed for use by community health workers, rather than an individual with a smartphone.

The Colonial present and the ‘common good’

Behavioural change explicitly contains assumptions of a ‘common good’ – aiming to induce individuals to make ‘better’, more efficient and healthier choices. The increasing implementation of these techniques in the global South raises ethical questions about the translation of ‘common goods’ and meanings of health and wellbeing from one setting to another – and also about the appropriateness of ‘global’ digital technologies being applied to ‘local’ ‘problems’. The cultural assumptions written into psy-technologies are often overlooked, meaning such technologies seem only open to challenge from insiders. Yet, while many technologies are new, they are embedded in historical conditions often linked to colonial governance.

Speaking of the Cashless Debit Card, one indigenous Australian participant said the card reminded them of the ‘ration days’, when the settler state regulated access to goods such as sugar, flour and tobacco. In India, too, governance through numbers and technologies was central to colonial rule. This alerts us to the need for historical, archival and post-colonial research to trace how technology and data are already implicated in shaping our social worlds.

The second phase of our project will explore the political forces that produce and legitimate certain forms of knowledge, digging deeper into the historical conditions of the British Empire that enabled the development of psy-technologies in each case site. This investigates the neglected ‘global coloniality’ of psy-technologies, arguing that this historical dimension affects not only on the reception of these technologies, but fundamentally structures how behaviour and psychologies are understood and governed.

Dr China Mills is Lecturer in Critical Educational Psychology at the University of Sheffield and Principal Investigator on the British Academy-funded project ‘Psy-technologies as global assemblage: histories and social lives of quantification and digitisation in three former countries of the British Empire’. The project is funded under the Academy’s Tackling the UK’s International Challenges scheme, which was launched in 2016 and aims to deliver excellent research with relevance to public and policy debates. Dr Elise Klein (research project Co-Investigator) is a Lecturer in Development Studies at the University of Melbourne.