10-Minute Talks: Choosing a title – George Eliot and "The Mill on the Floss"

by Professor Rosemary Ashton FBA

28 Apr 2021

Subscribe to this podcast via your chosen service

Professor Rosemary Ashton FBA discusses George Eliot's The Mill on the Floss in the wider context of novel writing and title choosing.

Transcript

Hello, I'm Rosemary Ashton, Emeritus Professor of English Language and Literature at University College London. I'm going to talk briefly today about George Eliot. My title is "Choosing a Title – George Eliot and The Mill on the Floss."

Novelists have often struggled with an important decision: what should my title be? The simplest and most commonly adopted answer to this question has been to name the work after its main protagonist. This has been the case from the beginnings of the English novel in the 18th century, with Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, to the novels of Fanny Burney and Jane Austen, to the heyday of the Victorian novel, with Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Jane Eyre, and George Eliot’s first novel Adam Bede, published to acclaim in 1859. The reason is not far to seek. Many novels follow the life and adventures, the successes and failures, of a single character, usually a young man or woman learning to navigate the world through trial and error. The German term bildungsroman is difficult to translate precisely, but it means a novel of learning and growing, was adopted early on in Britain from the description given to Goethe’s influential novel, Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, which was published in 1795. George Eliot’s second novel, The Mill on the Floss, might have been named after its main protagonist, Maggie Tulliver. It received its final title only after much hesitation. I’ll try to explain why in what follows.

The novel as a genre allows the author to range widely, both to inhabit a single consciousness and to cast an eye on the wider society in which the protagonist exists, to study the interrelations of the individual with family, class, society, time and place. George Eliot does this more thoroughly than probably any other novelist. In critical essays published in the years immediately before she began writing fiction, she offered a kind of manifesto for literature, especially for what she called "our social novels" (what she had in mind here was recent novels by Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, and Charles Kingsley, all concerned with the conditions of England at the time and with social problems). Her call is for realism, truth to life, to be achieved by imaginative means. In her view, the imagination has a moral as well as an aesthetic function; it should encourage understanding and fellow-feeling. In an essay printed in the Westminster Review in 1856 she wrote:

"The greatest benefit we owe to the artist, whether painter, poet, or novelist, is the extension of our sympathies…Art is the nearest thing to life; it is a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow-men beyond the bounds of our personal lot."

Here, in this essay, and in practice in her novels, we readers are invited to recognise our shared humanity as we engage imaginatively with fictional characters, including unheroic and dislikeable ones. George Eliot as narrator enters into the hearts and minds of a large number of her characters, major and minor, rather than concentrating all her sympathy on the "hero" or "heroine". In this she departed from the more usual practice – Dickens’s, for example – of creating "flat", unchanging characters whose chief function is to illuminate the life of the "round", or three-dimensional, character at the centre of attention, and these terms, "flat" and "round", I borrow from E.M. Forster’s famous distinction in Aspects of the Novel, published in 1927. By this criterion Mr Micawber is a "flat" character while David Copperfield is a "round" one. For George Eliot, who liked all her characters to be round (or at least to tend towards roundedness), an individual name did not always suit as a title. Sometimes a place name seemed the better choice, as it did with The Mill on the Floss and her later masterpiece, Middlemarch. The emphasis could then be as much on multiple relationships and the social environment as on the individual.

George Eliot began writing The Mill on the Floss in 1859, while Adam Bede was being praised to the skies as a work of genius and speculation was rife about who this unknown "George Eliot" might be. The author, Marian Evans, born in Nuneaton in 1819, was full of anxiety, not only about whether her second novel would be as good as her first – she suffered all her writing life from crippling self-doubt – but also about the rumours and the unwelcome unveiling of her pseudonym. She had good reason to worry, for she was living with a married man, the writer and journalist George Henry Lewes. With Lewes she gained love and loyalty and devoted encouragement to her genius; he regularly corresponded with her publisher John Blackwood, asking him to deal carefully with her fragile ego. As he told Blackwood in 1872, while she was halfway through writing Middlemarch, she was "thin with misery", feeling that her best writing was behind her and "what is now in hand is rinsings of the cask!", according to Lewes's view of what she was feeling.

Marian Evans’s experience of the anxiety of authorship was exacerbated by the odium which attached itself to her over her relationship with Lewes. Her much loved older brother Isaac Evans had cut off all contact with her on hearing about the liaison and society at large was disapproving. As an American visitor, Charles Eliot Norton, told a friend back home in 1869, by which time George Eliot was already famous, she "not received in general society", while Lewes was.

If this was true in 1869, it had been a searingly painful fact in 1859, when Marian Evans’s pleasure at the success of Adam Bede was all but overwhelmed by the dread of discovery mingled with righteous anger at the attitude of the world, and in particular "the world’s wife", towards "irregular" relationships like hers. The world’s wife is given its voice by a bitterly sarcastic narrator towards the end of The Mill on the Floss, when the main protagonist, Maggie Tulliver, returns home from a near-elopement with her cousin’s fiancé, Stephen Guest. Far worse for Maggie than the world’s wife’s disapproval is that of her unforgiving older brother Tom, who refuses to take her back into the family mill, which he has worked hard to regain after its loss by their debt-ridden father. "You will find no home with me", he says, barring her way. "You don’t belong to me".

The Mill on the Floss was the nearest to an autobiographical work of fiction that Marian Evans wrote. When we consider that she wrote it at the very time of the unwanted lifting of the incognito, we may well wonder at the humour and wise humanity shown by the author even as she lashes out at the small-mindedness and hypocrisy of social attitudes towards relations between the sexes. Cruel tongues wag when Maggie returns alone, not married to Stephen Guest. The narrator accepts that "we judge others according to results; how else? – not knowing the process by which results are arrived at". Yet her criticism of such a rush to judgment without knowing the full circumstances stands. In her mind was the fact, which could not be articulated directly in the novel, that those who judged her life choices did not know of Lewes’s circumstances, namely that his wife was by now the mother of four children by his best friend as well as the three who were his, and that he nevertheless continued to support the family financially. In her novel she demonstrates the unfairness of judging others peremptorily, and especially of judging women more harshly than men, a subject painfully understood from her own personal circumstances.

If it was unusual for George Eliot to write autobiographically, it was also unusual for her to give her novel a tragic conclusion. In this case the death of Tom and Maggie Tulliver in the flood which sweeps through the town of St Ogg’s. Such high drama did not sit well with her view that novels should truthfully represent everyday, ordinary life. Her difficulties over the title, which lasted almost until the novel went to press, are intimately connected with this dilemma she faced over how to end it. The provisional title had long been Sister Maggie. This was appropriate to the first part of the novel, which lingers long over the childhood of Maggie and Tom at the mill, threatening to overbalance the later part with its romantic entanglements when brother and sister become young adults. The scenes of childhood arguments and dramas – a fiery Maggie cutting her hair after having her appearance denigrated by critical visiting aunts; the amusing episode of the sharing of jam puffs baked by their mother, when Tom tries to cut one in equal parts to share with Maggie; Maggie forgetting to feed Tom’s rabbits while he is away at school and incurring his wrath on his return – these scenes are among the novel’s most impressive and much loved by readers. Some of the episodes, and Maggie’s feelings of rejection and injustice, were taken directly from Marian Evans’s own intensely experienced childhood with her brother Isaac.

But Sister Maggie, though appropriate thus far, was too narrow a title to fit the larger sweep of the novel. Lewes suggested The House of Tulliver, drawing attention to the tragic aspect of the human relationships, mainly that between Maggie and Tom, close but always thwarting one another, and dying young, but also the unfortunate neighbourly dispute in which their father, the hasty miller, engages before dying overwhelmed by disappointment and shame at the loss of the mill. Lewes’s suggestion, with its echo of the Greek story of the curse on succeeding generations in the House of Atreus, picks up on the allusions to Greek tragedy which run through the novel. At one point, foolish Mr Tulliver is compared to Oedipus, and George Eliot writes movingly of the tragedy that can ruin the lives of "insignificant people" like the "proud and obstinate miller" just as much as the lives of kings and queens.

Yet a tragic title puts too much stress on negativity and points away from realism and towards melodrama. George Eliot believed in the general progress of society and individuals, thanks to advances in knowledge which, properly directed, could improve the lot of the poor and widen education generally. And she believed that literature should reflect this progress. Individual tragedies do occur within such a representation of life, but do not sum it up. Though the death of two young people with whose lives we have been engaged throughout is the undoubted dramatic climax of The Mill on the Floss, the actual ending invites us to look through a wider lens. "Nature repairs her ravages", writes the narrator in the conclusion, describing the return of corn stacks and hedgerows in the years after the flood. Similarly, people’s livelihoods are rebuilt: "The wharves and warehouses on the Floss were busy again, with echoes of eager voices, with hopeful lading and unlading". Shortly before publication of the novel in April 1860, George Eliot accepted her publisher John Blackwood’s suggestion and called her work The Mill on the Floss, that being the most accurate title for a work which, while embracing both tragedy and comedy, also has room for comedy and good news, and also considers individual lives in the context of society at large. Finally, I would suggest also that though the novel might very well have been named after Maggie Tulliver, that would have been too painful a choice for its author.

This talk originally took place on 22 April 2020, part of the series The British Academy 10-Minute Talks, where the world’s leading professors explain the latest thinking in the humanities and social sciences in just 10 minutes. 10-Minute Talks are screened each Wednesday, 13:00-13:10, on YouTube and available on Apple Podcasts. Subscribe to the British Academy 10-Minute Talks here.

Further reading

British Library profile of George Eliot.

"What George Eliot’s ‘provincial’ novels can teach today’s divided Britain", article in The Guardian.

George Eliot's Ugly Beauty, article in The New Yorker.

George Eliot Poetry Foundation profile.

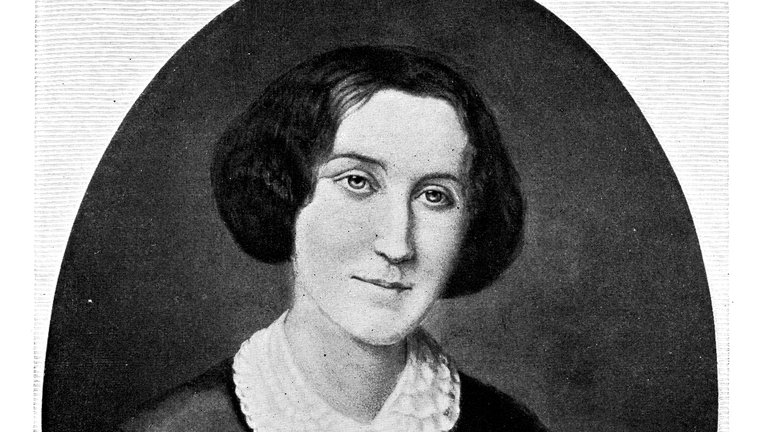

Lead image: George Eliot – Scanned 1899 Engraving. © benoitb via Getty Images.